Abstract

Objective

Hypertensive crisis is an increasingly frequent medical condition in our context. Its management in medical emergencies is a real challenge for physicians. Few data on hypertensive crisis are available in Chad. The aim of this study was to investigate the epidemiological, clinical and prognostic characteristics of hypertensive crisis in the medical emergency department of Reference National Teaching Hospital in N'Djamena.

Patient and methods

This was a prospective cohort study running from 1er March 2020 to October 31 2020. Patients presenting with a sudden and severe rise in blood pressure (systolic ≥ 180 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥ 110 mmHg) with or without acute target-organs damage, had been consecutively included and followed up over a period of one (01) month. Epidemic and clinical characteristics on admission, and morbidity and mortality parameters during the course of the disease were collected. The Kaplan-Meier method and the Cox model were used to analyze survival and factors associated with death, with a significance level of p<0.05.

Results

Of the 3978 hypertensive patients admitted to medical emergencies, 252 had a hypertensive crisis, i.e. a prevalence of 6.3%. Two hundred and seventeen (217) patients were included in the study, divided into 149 cases (69%) of hypertensive emergency and 67 cases (31%) of hypertensive hypertensive urgencies. The mean age of the patients was 55.2 ± 14 years (20 and 80 years) and 67% were male. Hypertension was known in 138 patients (64%). At least one complication was present on admission in 69% of patients. Complications were classified as cardiac (50.7%), neurological (38.2%), kidney impairment (46.5%) and ocular (46.1%). The average number of antihypertensive drugs used was 2 ± 0.83 1, 4. Calcium antagonists (86.5%), diuretics (35.5%), converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor antagonists (33.3%) and betablockers (18%) were the pharmacological classes prescribed. Good compliance during follow-up was observed in 124 patients. One-month survival was 84% for all patients, with a 16% mortality rate. Factors associated with death were the duration of hypertension, and the occurrence of cardiovascular, renal dysfunction and ocular disease (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Hypertensive crisis is a frequent pathology in sub-Saharan Africa, with high morbidity and mortality. Prevention requires early detection and effective management of hypertension.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Sasho Stoleski, Institute of Occupational Health of R. Macedonia, WHO CC and Ga2len CC

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2024 Naibé Dangwe, et al

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Arterial hypertension (AH) is a non-communicable, systemic disease that constitutes a genuine global public health problem 1. It is known to be more frequent, earlier and more severe in Sub-Saharan African populations 2. It takes a variety of forms, some of which are genuine medical emergencies 3, 4. One of these, the hypertensive crisis (HC), is very frequent and corresponds in most cases to the inaugural episode of arterial hypertension 5, 6. HC, which is a sudden and severe rise in blood pressure (systolic above 180 mm Hg and/or diastolic above 110 mm Hg) with or without acute target-organs damage, is subdivided into hypertensive emergency (HE) and hypertensive urgenvies (HU) 5, 7, 8. The presence of symptoms such as headache, epistaxis and ringing in the ears may be observed. In most cases, however, hypertensive crises are characterized above all by visceral damage 6, 9, 10, 11. In Chad, hypertension is common and is the main reason for hospitalization in cardiology 12. Delays in diagnosis and inadequate management explain the unfortunately still high prevalence of severe forms of hypertension 13. HC is an increasingly frequent medical condition, whose management in medical emergencies is a real challenge for doctors in our context. The lack of sufficient or up-to-date data on hypertensive crises led us to conduct this study, the aim of which is to investigate the epidemiological, clinical and evolutionary characteristics of HC at the Reference National Teaching Hospital in N'Djamena, Chad.

Patient and methods

This was a prospective cohort study conducted in the medical emergency department of the Reference National Teaching Hospital in N'Djamena, among patients admitted for a HC (systolic blood pressure above 180 mm Hg and/or diastolic above 110 mm Hg, with or without acute target-organs damage). The study was conducted in two phases:

an eight-month collection phase from March to October 2020;

a follow-up phase lasting one month from the date of study entry.

During the in-hospital management process, patients were transferred to specific department (cardiology, neurology, nephrology or intensive care unit) afterwards. We consecutively included all patients admitted to the medical emergency department of the Reference National Teaching Hospital for a HC, who consented to participate in the study. Hypertensive pregnant women were not included. The study consisted in collecting data on patients in the medical emergency department and data on patients admitted to inpatient wards, in order to assess patient progress up to discharge. It was carried out with the following considerations in mind :

The day of inclusion was considered to be D0, and the patient's clinical examination on that day constituted the baseline examination. During the initial examination, clinical and para- clinical data were collected;

The patient was seen again at D1 for an assessment of his management and the progress of his disease;

After transfer to a hospital ward, the data collected was updated and the new descriptions were taken into account;

The patient's mode of discharge was recorded;

We did not interfere with patient care (prescriptions for drugs and complementary tests);

Patients were withdrawn from the study, without explanation and without any consequences for their care.

Data collected included socio-demographic (age, gender, place of residence and education level), clinical (symptoms on admission), paraclinical (biological and imaging tests), therapeutic (type and number of antihypertensives drugs) and evolutionary (duration of hospitalization, outcomes and mode of discharge) characteristics.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using EPI INFO software version 7 and R software version 3.2.2. Quantitative parameters were presented as mean ± standard deviation, and qualitative parameters as percentages. Pearson's Chi2 test was used to compare proportions. When application conditions were not observed, Fisher's exact test was used. The Student's T-test was used to compare two means. The threshold of statistical significance was p<0.05. The Kaplan- Meier method was used to construct curves, and the Log Rank test to compare survival between groups. The Cox model was used to study factors associated with death.

Ethical considerations

The Reference National Teaching Hospital ethics committee approved the research protocol. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from patients prior to inclusion in the study. Participation in the study offered no direct benefit to the patient, and did not expose him/her to any additional risk other than those associated with his/her care. The study did not require the physician to perform any additional procedures other than those he or she was undertaking for the patient concerned. In the event of a treatment being contraindicated or poorly tolerated by a patient, the attending physician would be informed and would give the appropriate management instructions.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

During the study period, a total of 3,978 patients were admitted to the medical emergency ward, of whom 252 presented with a HC, representing a prevalence of 6.3%. Two hundred and seventeen (217) patients were included in the study, of whom 150 (69%) were HE and 67 (31%) were HU. The average age of the patients ranged from 20 to 80 years, with a mean of 55.2 ± 14 years, and they were predominantly male (67%). Socio-demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Arterial hypertension (AH) was known in 138 patients (64%), of whom 115 cases (53%) had already received antihypertensive drug. The mean duration of hypertension in these patients was 3.9 ± 5.9 years (1; 30 years). Thirty-seven of these patients (17%) had a known previous complication, distinguished as stroke (13 cases), chronic renal failure (18 cases), hypertensive retinopathy (six cases). Obesity (48.4%) and diabetes (16.6%) were the most common associated cardiovascular risk factors. Patients baseline characteristics did not statistically differ in terms of age, gender, level of blood pressure, average duration of AH and major cardiovascular risk factors between HE and HU. The cardiovascular risk factors associated with hypertensive crisis are shown in Table 2.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of patients| Features | HC | HE | HU | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 217 | 150 | 67 | |

| Average age (years) | 55,2 ±13 | 55,2± 14 | 55± 12 | 0,92 |

| Gender n (%) | ||||

| Male | 145 (67) | 97 (65) | 48 (72) | |

| 0,2 | ||||

| Female | 72 (33) | 53 (35) | 19 (28) | |

| Level of education n (%) | ||||

| Out of school | 72 (33) | 44 (29) | 28 (42) | |

| Primary | 19 (9) | 13 (9) | 6 (9) | |

| 0,1 | ||||

| Secondary | 56 (26) | 37 (25) | 19 (28) | |

| Superior | 70 (32) | 56 (37) | 14 (21) | |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | HC | HE | HU | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Former AH n (%) | 138 (64) | 104 (69) | 34 (51) | <0,01 |

| Average duration of AH (years) | 3,9 ± 5,9 | 4,4 ± 6,2 | 2,9 ± 4,4 | 0,09 |

| Diabetes n (%) | 36 (17) | 26 (15) | 10 (15) | 0,4 |

| Alcohol n (%) | 24 (11) | 13 (9) | 11 (16) | 0,08 |

| Obesity n (%) | 75 (35) | 48 (32) | 27 (40) | 0,2 |

| Tobacco n (%) | 21 (10) | 7 (5) | 14 (21) | 0,49 |

| Sedentary lifestyle n (%) | 30 (14) | 20 (13) | 10 (15) | 0,45 |

| Dyslipidemia n (%) | 30 (14) | 6 (4) | 24 (36) | 0,12 |

| NSAID n (%) | 23 (11) | 16 (11) | 7 (10) | 0,58 |

Clinical and paraclinical characteristics

Headaches and dyspnea were symptoms predominantly reported with respectively 53 % and 28 % of HC cases with nt statistical difference between HE and HU. However, precordialgia was more prevalent in HE (p=0,03) and palpitation in HU (p=0,03). (SBP) was 207.9 ± 21.4 mmHg (180; 260 mmHg). Patients with HE had a mean SBP of 209.2 ± 22.8 mmHg (180; 260 mmHg) and those with HU a mean SBP of 205 ± 17.6 mmHg (180; 240 mmHg) (p=0.02). Mean diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was 121.4 ± 13.9 93; 180 mmHg. Patients with a HE had a mean DBP of 121.6 ±14.6 mmHg (93; 180 mmHg) and those with a HU a mean DBP of 120.9 ± 12.4 mmHg (100; 150 mmHg) (p=0.02). Physically, heart failure and neurological deficit were found in 42% (n=91) and 21% (n=46) of cases respectively in HC. Every HE patient had at least one acute target organ damage. Among these patients with HE, 78 (52%) had acute heart failure and 37 (25%) motor deficit damage. None of patients with HU had acute target organ damage at baseline (Table 3). Biologically, mean hemoglobin was 11 ± 2.8 g/dl (1 ; 16 g/l), mean fasting blood glucose 1.3 ± 0.7 g/l (0.45 ; 10 g/l) and mean creatinine 50.5 ± 80.8 µmol/l (2; 341 µmol/l) with mean glomerular filtration rate (GFR) calculated according to the MDRD formula at 57.8 ± 40 ml/min/1.73m2 (2; 123ml/min/m2 ). A glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 60ml/min/1.73m2 was found in 101 patients (46%). Renal impairment was most important in HE patient than those with HU (p<0,001). electrocardiogram showed left atrial hypertrophy in 28 cases (14%), left ventricular hypertrophy in 45 cases (22%), myocardial ischemia in 34 cases (17%) and atrial fibrillation in nine cases (4%). Cardiac Doppler ultrasonography revealed concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricular walls in 24% of cases. At least one complication was present on admission in 69% of patients (n=150). Complications were classified as cardiac (51%), neurological (38%), renal (46%) and ocular (46%). Table 3 shows the clinical and paraclinical characteristics of patients on admission.

Table 3. Clinical and paraclinical characteristics of patients on admission| Features | HC | HE | HU | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||||

| Headache n(%) | 116 (53) | 77 (51) | 39 (58) | 0,38 |

| Precordialgia n(%) | 16 (7) | 15 (10) | 1 (1) | 0,03 |

| Dyspnea n(%) | 60 (28) | 47 (31) | 13 (19) | 0,07 |

| Vertigo n(%) | 20 (9) | 14 (9) | 6 (9) | 0,16 |

| Palpitation n(%) | 19 (9) | 9 (6) | 10 (15) | 0,03 |

| Visual impairment n(%) | 19 (9) | 13 (9) | 6 (9) | 0,94 |

| Buzzing n(%) | 5 (2) | 3 (2) | 2 (3) | 0,65 |

| Epistaxis n(%) | 10 (5) | 4 (3) | 6 (9) | 0,41 |

| Average SBP (mmHg) | 207,9 ± 21,4 | 209,2 ± 12,8 | 204 ± 17,6 | 0,17 |

| Average DBP (mmHg) | 121,4 ± 13,9 | 121,6 ± 14,6 | 120 ± 12,4 | 0,73 |

| Impaired consciousness n(%) | 32 (15) | 28 (19) | 4 (6) | 0,01 |

| Motor deficit n(%) | 46 (21) | 37 (25) | 9 (13) | 0,06 |

| Heart failure n(%) | 91 (42) | 78 (52) | 13 (19) | <0,001 |

| Paraclinical signs | ||||

| Average GFR (ml/min) | 57,8 ± 40 | 45,7 ± 37,8 | 84,2 ± 31 | <0,001 |

| Hemoglobin Tx (g/dl) | 11 ± 2,8 | 10,6 ± 2,9 | 12 ± 2 | 1 |

| Blood glucose (g/l) | 1,3 ± 1,1 | 1,42 ± 1,3 | 1,1 ± 0,4 | 0,04 |

| Fundus (n = 181) | ||||

| Normal n(%) | 87 (40) | 40 (32) | 47 (82) | |

| Kirkendall I n(%) | 31 (14) | 29 (23) | 2 (3) | |

| Kirkendall II n(%) | 41 (19) | 35 (28) | 6 (10) | <0,001 |

| Kirkendall III n(%) | 22 (10) | 20 (16) | 2 (3) |

Therapeutic aspects

All patients had received dietary advice and antihypertensive medication, with a mean number of antihypertensives of 2 ± 0.8 1, 4 (Table 4). Pharmacological management of HC comprised calcium channel inhibitors (86%) and diuretics (35%). Intravenous nicardipine was the only form of intravenous antihypertensive drugs available in our setting, it had been used in majority of patients with HU (87%) before as witch to oral medication form.

Table 4. Therapeutic characteristics of our patients| Features | HC | HE | HU | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological treatment | ||||

| Average number anti-HTA | 2 ± 0,8 | 2,3± 0,7 | 1,4± 0,7 | |

| Monotherapy n(%) | 45 (21) | 15 (10) | 30 (45) | |

| Dual therapy n(%) | 85 (39) | 58 (39) | 27 (40) | |

| Triple therapy n(%) | 62 (29) | 42 (28) | 20 (30) | NS |

| Quadritherapy n(%) | 25 (11) | 17 (11) | 8 (11) | |

| Pharmacological classes | ||||

| Diuretics n(%) | 77 (35) | 69 (46) | 8 (12) | <0,001 |

| Beta-blockers n(%) | 39 (18) | 37 (25) | 2 (3) | <0,001 |

| ACEI/ABAII n(%) | 72 (33) | 62 (41) | 10 (15) | <0,001 |

| Inhibitors n(%) Calcium | 188 (86) | 130 (87) | 58 (87) | 984 |

| Central Anti HTA n(%) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | - | - |

Evolutionary aspects

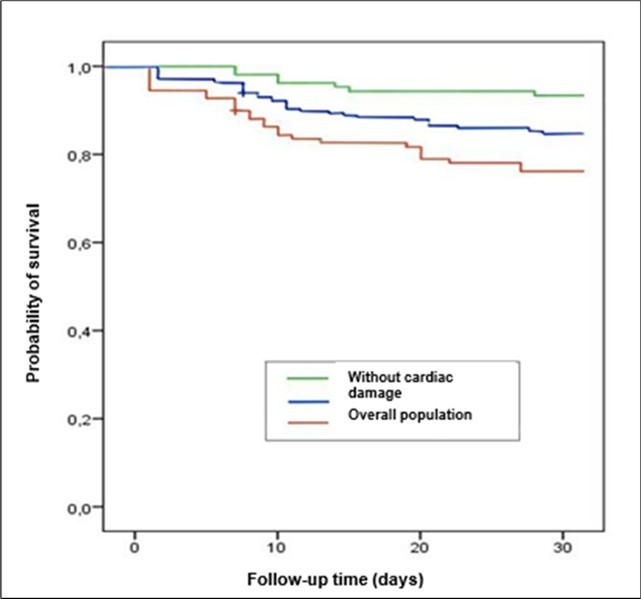

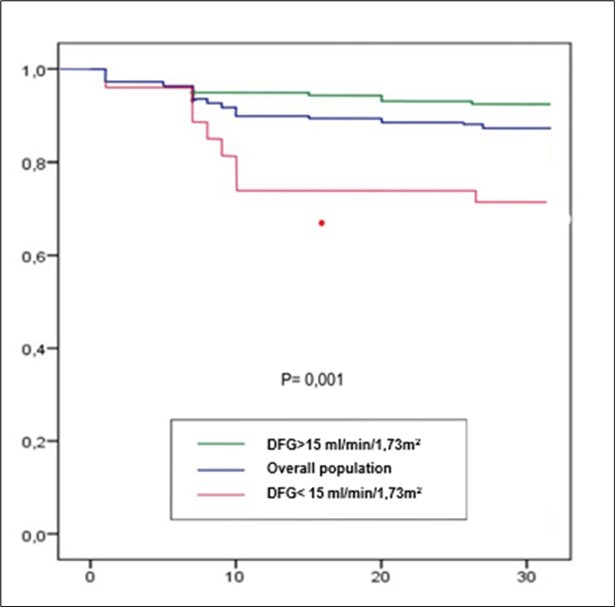

The average length of stay in the medical emergency department was 0.83 days with extremes of one (01) and four (04) days. The average stay in a specialist department was 11.24 days, with extremes of one (01) and 30 days. During the course of our study, we recorded 35 deaths, representing an overall mortality rate of 16% in HC. The factors associated with mortality in univariate analysis are summarized in Table 5, and Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the overall survival curve according to target organ damage.

Table 5. Univariate analysis of factors related to patient mortality| Death factors | Deaths | Relative risk (RR) | Confidence interval | P |

| Male (145) | 21 | 0,74 | 0,40-1,38 | 349 |

| Age > 65 (49) | 12 | 1,79 | 0,96-3,33 | 71 |

| Age < 45 (41) | 10 | 1,72 | 0,90-3,29 | 110 |

| Previous hypertension (138) | 26 | 1,65 | 0,82-3,35 | 151 |

| Kidney damage (101) | 21 | 1,72 | 0,93-3,21 | 0,81 |

| - GFR<15 (53) | 18 | 4,85 | 2,45-9,59 | 1 |

| Cardiac damage (110) | 28 | 3,89 | 1,78-8,52 | 1 |

| - OAP (20) | 6 | 2,03 | 0,96-4,31 | 0,07 |

| - IDM (25) | 3 | 1,866 | 0,96-3,61 | 0,07 |

| Eye damage (100) | 26 | 3,38 | 1,66-6,87 | 1 |

| - KK stage II(32) | 7 | 1,14 | 0,54-2,42 | 733 |

| - KK stage III(22) | 12 | 4,62 | 2,69-7,94 | 0 |

| HTA surge (67) | 0 | # | # | |

| 0 | ||||

| HTA emergencies (150) | 35 | # | # | |

| Malignant hypertension (50) | 13 | 1,94 | 1,07-3,63 | 733 |

| Transfer to specialized departments (201) | 29 | 0,39 | 0,188-0,788 | 16 |

| Abdominal obesity (96) | 14 | 0,84 | 0,45-1,56 | 581 |

| Taking NSAID (23) | 2 | 0,51 | 0,13-1,99 | 305 |

Figure 1.Overall survival curve for patients with hypertensive crisis as a function of cardiac involvement

Figure 2.Overall survival curve for patients with hypertensive crisis as a function of renal impairment

Discussion

These data show for the first time the epidemiological pattern of hypertensive crises in an adults’ medical emergencies department in Chad. In our study, the prevalence of HC was 6.3%. Naibé et al. in 2017 had already reported high prevalences (17.3%) of severe AH in their series on super AH 13. This result is similar to that Ngongang and al. in Cameroon, reported in 2019. HC was involved in 5.6% of cases 14. Mandi and al. in Burkina Faso in 2019 in their study about HC had recorded a higher prevalence (13.2%) 6. On the other hand, in the West, HC is clearly declining. Haythem at the CHU de Timone in France had found a prevalence of 0.97% 15. This low prevalence in the West could be explained by better organization of healthcare systems, improved access to specialist care for hypertensive patients, and early management of hypertension. The high prevalence in African series such as ours could be explained by :

· The increase in the prevalence of hypertension in the population, linked to galloping urbanization, which encourages an increasingly sedentary lifestyle, and to changes in our eating habits.

· Our patients' misperception of chronic illness in general, and hypertension in particular, which only becomes a concern at the complication stage.

· The absence of a national program to combat hypertension, which includes raising public awareness, early detection of hypertension and ongoing training of doctors in the management of hypertension in peripheral facilities.

The mean age of our patients was 55.2 ± 14 years. The relatively young age of our study population corroborates the data found by Naibé and al. who reported a mean age of 51 years 13. Mandi and al. in Burkina Faso found in their series an average age of 52.6 6. The proportion of hypertension occurring at an early age, being more severe and subject to numerous complications in black populations, has been demonstrated in African-Americans by numerous authors 16, 17, 18. This tendency to develop hypertension in our countries could be explained by a combination of several factors: genetic susceptibility, environmental risk factors, high consumption of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and street drugs, alcohol and tobacco.

In our series, at least one complication was present in 150 patients (69%). Complications were classified as cardiac (51%), neurological (38%), kidney impairment (46%) and ocular (46%). Mandi in Burkina Faso and Shao in Tanzania reported cerebral complications in 30% and 31% of cases respectively 6, 11. Boombhi and al. and Ngongang and al. found a high prevalence of kidney impairment in 79% and 78% of cases respectively 14, 19. This diversity of results could be taken in its entirety as the end result of arterial hypertension when it is untreated or poorly treated. Indeed, as a silent killer, hypertension spares no organ when it is not optimally managed.

The mean number of antihypertensive drugs was 2 ± 0.8 1; 4. Dual therapy was prescribed in 68% of cases in our study. This trend towards dual therapy was also found by Mungawo in his Kampala series 20. Our results are in line with the guidelines of learned societies in the management of hypertension. Indeed, William and al. recommended dual therapy as the first- line treatment, especially when the cardiovascular risk is high 21. The aim of combining antihypertensive drugs is to lower blood pressure rapidly, depending on the indications, in order to avoid complications. This combination increases the cost of patient management. This cost of management makes compliance and follow-up of hypertensive patients all the more difficult in our context 1, 2.

The crude mortality rate in our study was 16.1% person-months, with a mean age of 35 years for patients who died. The presence of renal dysfunction, age under 45, and lack of awareness of hypertension were independent predictors of mortality. Several series on hypertensive crises also reported that lack of awareness of hypertension, male gender, young age, non-compliance with treatment and renal impairment were factors associated with higher mortality 19, 23, 24. Numerous agregate factors explain this high mortality rate in HC, such as delays in consultation and treatment, the low socio-economic status of our patients, the absence of health insurance and the precariousness of treatment resources.

Conclusion

Hypertensive crises are very common in our country. It affects young adults, with high morbidity and, mortality inadequacy of the therapeutic platform. Its management must be early and appropriate, in order to avoid the complications that worsen vital prognosis of these patients. In our context, emphasis must be placed on prevention and early detection of hypertension

References

- 1.Kearney P M, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton P K et al. (2005) Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. , Lancet 15, 217-23.

- 2.Yaméogo N V, Kagambèga L J, RCG Millogo, Kologo K J, Yaméogo A A et al. (2013) Factors associated with poor blood pressure control in black African hypertensives: a cross- sectional study of 456 Burkinabe hypertensives. Annales de Cardiologie et d'Angéiologie. 62(1), 38-42.

- 3.Levy P D, Mahn J J, Miller J, Shelby A, Brody A et al. (2015) Blood pressure treatment and outcomes in hypertensive patients without acute target organ damage: a retrospective cohort. Am J Emerg Med. 33(9), 1219-24.

- 4.Sylvanus E, Sawe H R, Muhanuzi B, Mulesi E, Mfinanga J A et al. (2019) Profile and outcome of patients with emergency complications of renal failure presenting to an urban emergency department of a tertiary hospital in Tanzania. BMC Emerg Med. 19-1.

- 5.Polly D M, Paciullo C A, Hatfield C J. (2011) Management of hypertensive emergency and urgency. Adv Emerg Nurs. 33(2), 127-36.

- 6.Mandi D G, Yaméogo R A, Sebgo C, Bamouni J, Naibé D T et al. (2019) Hypertensive crises in sub-Saharan Africa: Clinical profile and short-term outcome in the medical emergencies department of a national referral hospital in Burkina Faso. Ann Cardiol Angeiol. , (Paris) 68(4), 269-74.

- 8.Migneco A, Ojetti V, A De Lorenzo, Silveri N G, Savi L. (2004) Hypertensive crises: diagnosis and management in the emergency room. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 8(4), 143-52.

- 9.Talle M A, Doubell A F, PPS Robbertse, Lahri S, Herbst P G. (2023) Clinical Profile of Patients with Hypertensive Emergency Referred to a Tertiary Hospital in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Curr Hypertens Rev. 19(3), 194-205.

- 10.Fragoulis C, Dimitriadis K, Siafi E, Iliakis P, Kasiakogias A et al. (2022) Profile and management of hypertensive emergencies and emergencies in the emergency cardiology department of a tertiary hospital: a 12-month registry. , Eur J Prev Cardiol 19, 194-201.

- 11.Shao P J, Sawe H R, Murray B L, Mfinanga J A, Mwafongo V et al. (2018) Profile of patients with hypertensive urgency and emergency presenting to an urban emergency department of a tertiary referral hospital in Tanzania. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 18(1), 158.

- 12.madjid Zakaria Zakaria A, Ahamat Ali A, Sakadi F, Lucien A, Ali Ibrahim T. (2021) . Hospital Prevalence of Arterial Hypertension in the Cardiology Department of National Reference Teaching Hospital. CCR 5-2.

- 13.Naïbé D T, Mandi D G, Yaméogo R A, Mianroh H L, Kologo K J et al. (2017) Clinical and prognostic characteristics of super hypertension Prospective cohort study Ndjamena- cardiologie tropicale n°148 Avril-Juin;. 15-25.

- 14.Ngongang Ouankou C, Chendjou Kapi LO, Azabji Kenfack M, Nansseu J R, Mfeukeu- Kuate L et al. (2019) Severe high blood pressure recently diagnosed in an urban milieu from Subsahelian Africa: Epidemiologic, clinical, therapeutic and evolutionary aspects. Ann Cardiol Angeiol. , (Paris) 68(4), 241-8.

- 15.Guiga H. (2016) Prevalence and severity of hypertensive emergencies and relapses in the hospital emergency department of CHU La Timone de Marseille: three-month follow-up of hospitalized patients. , Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris),http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ancard.2016.04.005

- 16.Cherney D, Straus S. (2002) Management of patients with hypertensive emergencies and emergencies: a systematic review of the literature. , J Gen Intern Med 17(12), 937-45.

- 17.Chevallier A. (2006) Management of adult patients with essential hypertension. Journal des Maladies Vasculaires 31(1), 16-33.

- 18.Gronewold J, Kropp R, Lehmann N, Stang A, Mahabadi A A et al. (2021) Population impact of different hypertension management guidelines based on the prospective population- based Heinz Nixdorf Recall study. , BMJ Open 17, 11-2.

- 19.Boombhi J, JGK Mekontso, Nganou-Gnindjio C N, ELND Hedzo, GLN Tchoukeu et al. (2022) complications and factors associated with severely elevated blood pressure in patients with hypertension: a cross-sectional study in two hospitals in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Pan Afr Med. 42-20.

- 20.Mugwano I, Kaddumukasa M, Mugenyi L, Kayima J, Ddumba E et al. (2016) Poor drug adherence and lack of awareness of hypertension among hypertensive stroke patients in Kampala, Uganda: a cross sectional study. , BMC Res Notes 2, 3.

- 21.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M et al. (2018) ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 36(10), 1953-2041.

- 22.Márquez D F, Rodríguez-Sánchez E, JS de la Morena, Ruilope L M, Ruiz-Hurtado G. (2022) Hypertension mediated kidney and cardiovascular damage and risk stratification: Redefining concepts. Nefrologia (Engl Ed). 42(5), 519-30.