Abstract

Self-determination is a key concept to promote greater self-awareness in the subjects with disability, to build appropriate educational or professional projects and to evaluate the already active programs. Using PRISMA checklist, I selected articles from different databases (CINAHL, Medline, Psych INFO, Cochrane Library, ERIC, Scholar. The 9 evaluation measures identified are analyzed with respect to: choice of the points of view to be collected, domains, items and data collection methods.

The results show that while some scales focus on autonomy, empowerment, self-realisation and self-regulation and others focus on knowledge, skills and abilities, attitudes and beliefs. Two instruments added also: opportunities and support. With respect to the choice of the points of view to be collected: in some cases the student’s opinion is collected but in other cases their point of view is integrated or replaced with that of teachers and parents. Only one tool is designed for all children and starts from the belief that self-determination is important for all people, including those with a disability. A third element of the analysis is the possibility of answering the questions posed by the various evaluation tools. A typical form is Likert scale while in other cases open questions are used.

The analysis highlights two critical issues. The variety of definitions of self-determination is inevitably reflected in the choice of domains and items and therefore self-determination is only partially investigated. Secondly the opinion and people with disabilities are sometimes completed or replaced by that of third persons as parents and teachers.

Starting from the analysis of existing instruments. the article closes with a reflection on the possibility of constructing a scale that considers all the aspects of self-determination offered in the literature (at the individual and environmental level) and collects the opinion of all the subjects involved in self-determination projects. This synthesis represents a first step in the construction of a possible universal scale starting from the analysis of the literature. A comparison would then be necessary with the students with intellectual disabilities, the family members and the other actors involved to understand which domains are really meaningful to them and to build indicators that correspond to the elements that are important to them. In this way we would have a tool capable of combining the point of view of literature with that of the people directly involved.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Laura Orsolini, Psychopharmacology Drug Misuse and Novel Psychoactive Substances Research Unit, School of Life and Medical Sciences, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, UK.

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2019 Zappella Emanuela

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Since the beginning of the 90's, attention on the concept of self-determination in students with intellectual disabilities has increased 1. Learning and teaching self-determination can make a difference in people's lives 2 and improve their quality of life (QOL) 3, 4. The results obtained in the evaluation of self-determination, then, can be used to: promote a greater self-awareness in the subjects; build appropriate educational or professional projects based on needs; offer supports within the environment and evaluate already active programs 5, 6.

The four conceptual models of self-determination

In the literature there are different definitions of the concept of self-determination. In Luckner & Sebald’s opinion (2013) 7, for example, self-determination is defined by: awareness and self-knowledge; the possibility of making decisions; planning and achievement of objectives; problem solving; self-regulation and self-advocacy.

The lack of consistency in the definitions often creates confusion and misunderstanding, especially with those with severe disability 8. For this, Wehmeyer (2005) 9 specifies what self-determination is not. First of all, it is not synonymous with independent performance and absolute control, because men live in relationships of interdependence, and support from other students with intellectual disability does not preclude the possibility of controlling their actions. Precise self-determined behaviours do not necessarily lead to successful experiences because decisions are not always optimal, even when all possible choices, actions and solutions to solve any problems are identified and examined. Self-determination, then, is not synonymous with self-sufficiency, otherwise it would be difficult to approach students with intellectual disability with disabilities who, instead, sometimes need support to achieve their goals. Another common mistake is to consider self-determination as only skills or opportunities, while it depends on skills, opportunities and the presence of adequate supports. Self-determination, then, is not simply something that "is done," and cannot be linked to a specific result. There is nothing intrinsically self-determined, in fact, in being married, separated or single, in having a job or doing volunteer work. Finally, self-determination cannot simply be a synonym of choice; self-awareness, goal setting, decision-making and problem-solving skills are also important. These clarifications clarify the contours of the concept of self-determination which, according to the literature, can be described following four models.

Functional Model of Self-Determination

The model is based on the definition of Wehmeyer (2010) 10 according to which self-determination is the attitude and ability of students with intellectual disability to be the main agents within their life with the aim of improving their own Quality of life (e.g QOL). In this sense, individuals are the origin of their actions and, when they have great aspirations, they are able to persevere before obstacles and failures 11. The author, while recognising the importance of the environment, places more emphasis on the individual characteristics of the subjects, such as the development of new skills, rather than changes to be included in the environment 12. An action is self-determined when it has four characteristics: the individual acts autonomously; behaviours are self-regulated; the person begins and responds to events in order to favour their empowerment and the person acts in such a way as to favour self-realisation 13.

The four elements that define a self-determined behaviour are 14

Autonomy

act independently and in accordance with the preferences and interests of the subject;

Self-Regulation

skills relating to the definition of objectives and problem solving in the main contexts of one's life such as school and work;

Self-Realization

adequate knowledge of skills and limits;

Empowerment:

conviction of possessing the skills required to achieve set goals and control situations.

Ecological Model of Self - Determination

At the base of the ecological model is the proposal by Abery and Stancliffe (2003) 15 to highlight the role of the environment. According to these authors, personal skills are influenced by the environment which, in turn, is influenced by skills and self-determination depends on three interrelated elements: the desire for control, the degree of control actually exercised and the importance given at the various events. Within this construct, a person who has low control due to their disability can have a high level of self-determination if there is a close relationship between the desire for individual control and the importance of the result. The domains in this case are three:

Skills

goal setting, decision making, self-regulation, problem solving, personal advocacy, communication, social relationships and independent living;

Knowledge

of oneself and of one's own economic situation, of the rights, of the available resources, of the possible options when it comes to making a choice; attitudes and beliefs: locus of control, sense of effectiveness, self-esteem, self-acceptance, perception of being appreciated by others and positive prospects for the future.

The control of these domains is considered at four different levels: microsystem (family, school), mesosystem (relation between two microsystems), ecosystem (external influence of factors not directly attributable to the individual) and macrosystem (ideological and cultural level).

Model of Learning Self-Determination

Mithaug and colleagues (2002) 16 focus on the process that leads to self-determination, seen as the freedom to use resources to achieve goals consistent with their needs and interests expressed within a welcoming community. Specifically, the model explores how individuals interact with opportunities to improve their perspectives with respect to the goals they intend to achieve in their lives. In this case, self-determination is influenced by two domains:

Ability

understanding the meaning of self-determination, the behaviours necessary to exercise it, plan goals and make decisions;

Opportunities

places where self-determination is exercised, particularly in the home and school environment.

The challenges that the subjects live are opportunities to pursue their goals and learn how to adjust their thoughts, feelings and actions 17, 18. Self-determined students with intellectual disability learn to express needs, interests and abilities, to have goals and expectations and are able to change decisions and adjust behaviours to achieve the desired goals effectively.

Model of the Theory of Agency

Shogren and colleagues (2014) 19 review the functional model with two objectives: to extend it beyond the sphere of disability, recognising that self-determination is relevant for all subjects, including those with disabilities, and to integrate it with contributions from other disciplinary sectors, such as psychology 20. Unlike other theories on human behaviour, the theory of agency provides that the agent's action is: motivated by biological and psychological needs; directed towards self-regulated goals; driven by the understanding of agents, means and ends and triggered by contexts that provide supports and opportunities, as well as obstacles and impediments 21. The domains, which include those of the functional model plus other elements related to different disciplines are: voluntary action, agentic action and control of one's own beliefs and perceptions.

The functional model, and that of the agency that is a revisitation, emphasizes individual characteristics, while that of learning highlights the process by which students with intellectual disability can become more self-determined. Finally, the ecological model emphasizes the fundamental role of the environment. From the analysis of the four perspectives three common elements can be traced 22. the responsibility in the first person for one's own life which includes both direct and indirect control of situations; the effects of the environment and of the opportunities that influence the self-determination of the individual; the idea that making decisions is a broader concept than choosing from various options, but requires a range of skills necessary for self-determination.

The different definitions lead to the construction of different instruments, with different evaluations that, from time to time, privilege some components of self-determination, leaving others in the background.

The aim of this paper is to identify and systematically review self determination measures that could be used routinely by researchers and service providers in measuring self determination for students with intellectual disabilities. For each scale the following aspects are analysed: theoretical framework of reference, recipients, domains and items and methods of evaluation of self-determination. The items are then compared to identify similarities and similar thematic areas.

Methodology

The research concerns the articles published from the year 1990 to 2018 in the database: CINAHL, Medline, PsychINFO, Cochrane Library, ERIC, Scholar using a combination of the following keywords: self-determination evaluation, assessment, quality of life, self-determination scale, student with intellectual disability.

The evaluation tools (Annex 1) are inserted if they offer indications with respect to the theoretical framework of reference, to the recipients and possess a recognised reliability and validity.

I used the PRISMA checklist formed by 27 items: title, abstract (structured summary including background, objectives, data sources, study eligibility criteria, participants and interventions, study appraisal and synthesis methods, results, limitations, conclusion and implications of key findings, systematic review registration number); introduction (rationale, objectives); methods (protocol and registration, eligibility criteria, specify study characteristics used as criteria for eligibility), information sources, search, study selection, data collection process, data items, risk of bias in individual studies, summary measurement, synthesis of results), selection topic (risk of bias across studies, additional analyses); results (study selection, study characteristics, risk of bias within studies, results of individual studies, synthesis of results, risk of bias across studies, additional analysis); discussion (summary of evidence, limitations, conclusions); funding 23

In order to prevent bias, inclusion and exclusion criteria and all steps are described. Two independent raters conducted analysis. The two raters coded the data independently and then met to compare analyses. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. The following chart described the stage of the review process and exclusion and inclusion criteria figure 1.

Instruments

The main measurement scales of self-determination in the literature are briefly described below:

The Arc’s Self-Determination Scale 24

The authors start from the idea that making decisions without external influences and interferences is a key element in people's lives and offer a tool to evaluate the self-determination skills of adolescents with disabilities, in particular with a moderate cognitive delay.

The scale is designed to encourage greater self-determination through a first-person assessment of beliefs and beliefs about themselves, and working in collaboration with educators and other subjects to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the goals of self-determination and self-assessment of progress and results over time.

The instrument, which contains 72 items, is subdivided into four subscales: care of oneself and one's family; management of interactions with the environment; recreational activities and leisure time management, social and professional activities. We analyse:

Autonomy

the ability of an individual to make his own decisions, without interference or influence from others. Students are asked to respond as they would in a series of situations;

Empowerment

conviction of being able to reach their goals and have control over a situation and understanding of their strengths and weaknesses. Students must choose the answer (between two) that best describes themselves;

Sense of Self-Realization

students must declare that they are in agreement or disagreement with matters concerning themselves;

Self-Regulation

students must answer a series of questions regarding some real-life situations.

The questions can be administered in small groups (maximum 15 students at a time) and students can complete the scale independently or with the help of a teacher. According to the authors, people increase their self-determination by developing a series of characteristics such as: making decisions, solving problems, defining goals, self-evaluating, self-efficacy, locus of control. The score obtained from the scale can (Wehmeyer, 1995): help teachers and students to analyse areas of strength and criticality with respect to the issue of self-determination; generate discussions around the items that students consider interesting, problematic or simply want to discuss in more detail, and compare the total scores, domains and sub-domains and identify the elements of strength and criticality between the domains.

The Self-Determination Assessment Battery 25

The scale, developed from the model of Field and Hoffman, outlines the cognitive, affective and behavioural variables that can be controlled by the individual and can be the subject of educational intervention. The characteristic element of this tool is the choice to collect and compare the point of view of children with disabilities, teachers and parents. The domains are:

Self-Knowledge

dreams, strengths and weaknesses, needs and preferences, possible options, supports, expectations and decisions about what is important;

Self-Appreciation

accepting and evaluating oneself, appreciating strengths, recognising and respecting rights and responsibilities, taking care of oneself;

Planning

setting goals, planning actions to achieve them, predict results, be creative;

Action

risk, access resources and supports, manage conflicts and criticism; evaluation of the experience and learning: compare performance and expected results with real ones, recognise successes, introduce adjustments.

The instrument is divided into five scales: Self-Determination Knowledge Scale for the students, Self-Determination Parent Perception Scale and Self-Determination Teacher Perception Scale, a questionnaire for teachers and parents; Self-Determination Observational Checklist, an observation grid for teachers and Self-Determination Student Scale for the students. This scale favours the comparison between students, teachers and parents with respect to specific domains, helps the identification of the elements of agreement and discrepancy (for example regarding skills that are observable at home and not at school) and allows the comparison between student scores and also in relation to the "average score".

Choicemaker Self-Determination Assessment 26

The ChoiceMaker Self-Determination Assessment is designed for students with moderate disability and behavioural difficulties, although it can be adapted for the most severe disabilities. Self-determination exists when individuals can define their own goals and take the necessary steps to achieve them and cover the following areas: interests, abilities and limitations, goals and possibilities for action. The instrument is connected to Choicemaker Self-Determination Curriculum in which students can learn skills related to self-determination through a personalised plan. The tools are linked in the sense that the issues included in the first scale refer to the objectives defined in the second. In the ChoiceMaker Self-Determination Curriculum in which there are two levels of response, student skills and opportunities offered by the school, compared to:

Choose the Objectives

expressing objectives: guide for the meeting with the students, the moment in which, according to the American law, teachers, parents and professionals meet the student with disability to evaluate their progress, set goals for the future and decide in which school will they continue their training;

Choose to Act

divide the objectives into smaller actions, determine the motivations that drive to act in a certain way, identify the supports needed to complete the objectives, outline the timing and be convinced that the objectives can be achieved, evaluate objectives and define the introduction of possible adjustments.

The ChoiceMaker Self-Determination Assessment Consists of Three Parts

The ChoiceMaker Assessment: three sections that evaluate the skills and competences in 51 self-determination skills and the opportunities that the school makes available to encourage these behaviours;

The ChoiceMaker Assessment Profile: monitoring tool to graphically display student progress and highlight the opportunities they have to bring out these skills within the school;

The ChoiceMaker Curriculum Matrix: helps teachers to visually identify the skills in which the student needs to be supported.

Self- Determination Scale for College Students 27

Based on Wehemeyer’s Model, the Scale Contains 48 Items Organised Into 4 Sections

Self-Realization

awareness, perception and self-understanding (for example, I am aware of which university courses are most interesting to me);

Autonomy

independent life and self-care (for example, I can take notes and know where to look for useful information at school);

Empowerment

locus of control, self-advocacy, awareness of the desired results (for example, I believe I can complete the task successfully);

Self-Regulation

assessing people's ability to set goals, solve problems and adapt behaviours according to the situation (for example, my career goals are designed according to my interests).

Subjects, through a Likert scale, select the affirmation that most reflects their current situation or opinion and the score goes from 1 (decidedly disagree) to 5 (decidedly agree).

The American Institute for Research Self - Determination Scale 28

This tool, designed for students, educators and parents, evaluates students' self-determination with respect to three components: thought, action and adjustments. The scale, which can be used with students of all ages, offers information about the abilities and possibilities that students have of self-determination. At the base is a self-theory that explains how individuals interact with the opportunities presented to them to improve their chances of getting what they need and want in life. The scale is made up of three sections with respect to skills, measured in two contexts, at school and at home: knowledge (as the student recognises their strengths, needs, interests and abilities); ability (as the student demonstrates self-determination skills with respect to their own choices and action plans); perceptions (with respect to interests, needs, abilities and objectives).

The Format for Students Includes Five Sections

What I Do

evaluate how well they can perform certain tasks;

How I Feel

ask students to respond to how they feel about performing certain tasks related to self-determination;

What Happens at School/Home

self-determination opportunities at school and at home;

Open Questions

describe a goal they are pursuing, the actions they are taking and the feelings they are feeling.

The scale for parents and educators is similar to that proposed to students and requires to respond using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The tool helps to: evaluate and develop a profile of a student's self-determination level; determine the strengths and areas of improvement to increase self-determination; identify the goals to be achieved and develop strategies to increase students' skills and opportunities.

Minnesota Self-Determination Scales: Skills, Attitudes, and Knowledge Scale 29

This scale, for students and family members and educators, is made up of 90 items grouped into 8 domains and measures self-determination skills with respect to knowledge, skills and attitudes. The student version consists of 101 questions and asks to respond with "completely disagreeing, disagreeing, agreeing and completely agreeing". The scale for educators and parents is made up of 110 questions they are also asked to respond in a similar way (rarely, little, not very often, often, very often, always). There is also a scale that assesses the ability of the services to support students with intellectual disabilities with respect to: orientation; skills and knowledge; application of skills; training; quality of training; supervision; work habits of staff; abilities, attitudes and beliefs related to self-determination and knowledge that support it.

ARC-INCO Self-Determination Assessment Scale 30

This tool overcomes the limitations of adaptation produced in Spain (Verdugo et al., 2009; Wehmeyer et al., 2006) of the Arc Self-Determination Scale (Wehmeyer & Kelchner, 1995). Taking into account the review of strengths and weaknesses (Vicente et al., 2012), three sections (autonomy, empowerment and self-realisation) have remained unaltered. The most important change concerns the self-regulation section. Specifically, indicators of the self-determination scale of Hoffman and colleagues (2004) and a four-point evaluation system is used to facilitate use. The sections are:

Autonomy

compared to meals, clothing, self-care, public transport, involvement in pleasant activities, plans for the future, choice of how to spend money;

Self-Regulation

evaluation of activities, analysis of the various possibilities before deciding, awareness of what is important for oneself, ability to orient oneself in a new place, comparison between expectations and results;

Empowerment

communication of opinions and states of mind, making decisions about oneself, relational skills and socialisation, awareness of being able to carry out the work you want;

Self-Realization

concern to carry out the tasks correctly, acceptance of oneself, one's own strengths and problems and awareness of one's own abilities. Peper Transition Planning Scale 31

This tool, which is based on the concept of self-determination proposed by Abery and Stancliffe is made up of three domains: skills, knowledge and attitudes/beliefs. Before creating the questions, the authors examine the literature with particular attention to the Choicemaker Self- Determination Assessment and ARC’s Self-Determination Assessment, and talk with the teachers involved in the transition paths of their students. The key elements are:

Definition of Objectives

explain what a transition plan is and what are the objectives of personalised paths;

make decisions inside and outside the school environment, and awareness of the figures involved in the subject's project;

Solve Problems

how problems are solved and what are the factors;

Self-Awareness

limits and strategies that help achieve goals;

Communication

difference between passive, aggressive and assertive attitude and importance of non-verbal communication;

knowledge of rights, responsibilities and laws to protect persons with disabilities;

knowledge of available resources and state services;

Attitudes and Beliefs (Determination)

ways to achieve goals, face challenges and highlight progress;

Attitudes and Beliefs (Locus of Control)

the belief that we can achieve our goals;

Attitudes and Beliefs (Self-Esteem and Self-Concept)

description of the objectives achieved and understanding of motivations in the case of failure to achieve the objective.

ADIA 32

The scale includes some of the self-determination elements of people with disabilities followed by some examples. The survey concerns the domestic environment, the school (or the centre) and the community and the evaluation must be done using a Likert scale that goes from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The areas analysed are:

Perceptions and Knowledge

of their strengths, of the effects of their actions, of the difference between current and future situations;

skills

manifesting desires, making choices, planning goals, self-correcting;

Opportunities

the context offers the opportunity to manifest desires, plan objectives, make choices and self-retreat;

Support

support in adopting behaviours that go in the direction of meeting objectives, self-regulating behaviour, proposing ideas and plans.

Self-‐Determination Inventory: Self-‐Report 33

It is the first instrument that includes both the point of view of subjects with and without disabilities (between 13 and 22 years) and that of teachers and parents. The skills associated with self-determined action include: choice, problem solving, decision making, goal setting and achievement, self-advocacy and self-management skills; key attitudes, on the other hand, include consciousness and self-knowledge. With a better understanding of the self-determination given by the use of the scale, teachers can identify the targeted skills that support learning and implementation of all students. The three elements, for which we identify educational elements and strategies, are:

Intentional Action

making intentional and conscious choices based on preferences and interests. The two aspects investigated are autonomy and personal initiatives;

Agentive Action

self-directing and managing actions towards the pre-set objectives in terms of thinking about possible paths, defining the direction and self-regulating;

Beliefs of Control of Actions

belief in being able to use their skills and resources (for example, people, supports) to achieve a goal, empowerment (believe they have what it takes to achieve their goals) and self-realisation.

Results

Analysis and Comparison Between the Scales

A first element to consider when comparing the scales is the choice of the points of view to be collected: in 5 cases, the students with intellectual disabilities have to answer the questions, in 2 cases their opinion is integrated and in 1 case replaced with that of teachers and parents. The Self-Determination Inventory is the only tool designed for all children and starts from the belief that self-determination is important for all people, including those with a disability figure 2.

Figure 2.Number of the points of view collected

A second aspect to consider is the domains investigated, which depend on the definition of self-determination chosen by the authors. While some scales focus on the four elements (autonomy, empowerment, self-realisation and self-regulation) others focus on knowledge, skills and abilities, attitudes and beliefs figure 3.

Figure 3.Model of self determination used

The domains proposed by the different tools refer to both individual and context-related factors and can be summarised as follows.

Autonomy

ability to act on the basis of one's own preferences without external influences and to manage situations related to self-care and the concept of independent life;

Empowerment

conviction of being able to achieve their goals, locus of control, self-advocacy, awareness of the desired results;

Sense of Self-Realization

self-esteem, perception and self-understanding, strengths, limits and strategies that help achieve goals;

management and evaluation of the actions undertaken to achieve its objectives and reaction to the stimuli of the environment;

of the rights, responsibilities, laws to protect persons with disabilities, available resources and services;

Skills

defining goals, making decisions and solving problems, tackling challenges and highlighting progress;

opportunities: the context offers the opportunity to manifest desires, plan objectives, make choices and self-retreat;

support in adopting behaviours that go in the direction of meeting objectives, self-regulating behaviour, proposing ideas and plans.

With respect to the items, some common factors emerged from the analysis as indicated below. A first key element is attitudes described as: locus of control, self esteem, self concept and understanding motivation in the case of failure figure 4.

Figure 4.Categories about attitudes

A second key point that emerged is action defined as: planning action/choose to act, setting actions, expressing goal, predict results, manage conflicts and criticism figure 5.

Figure 5.Categories about action

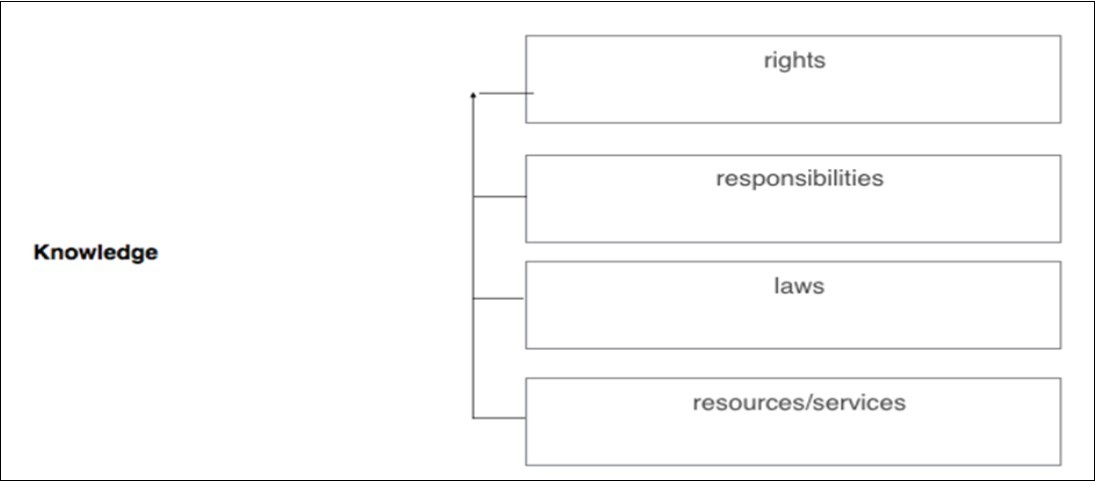

A third key point is knowledge defined as: rights, responsibilities, laws and resources/services figure 6.

Figure 6.Categories about knowledge

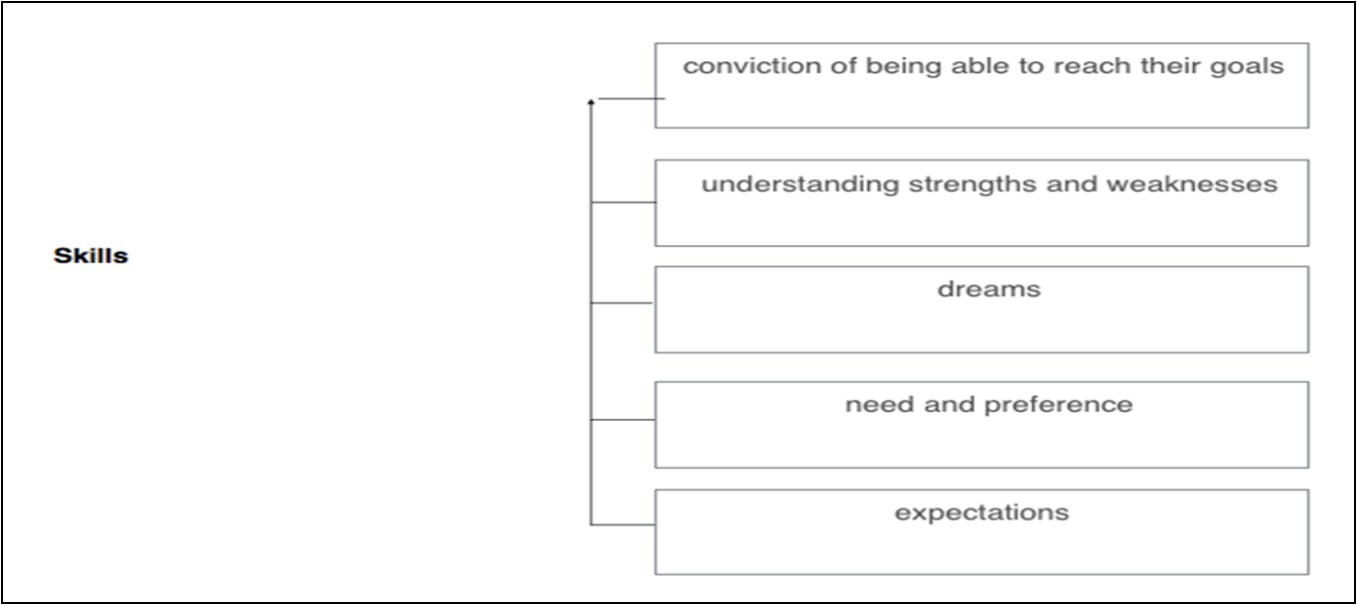

Another key point is about skills: conviction of being able to reach the goals, understanding strengths and weaknesses, dreams, need and preference and expectation figure 7.

Figure 7.Categories about skills

After skills, the last key point is evaluations (what they can perform, experience and learning, objective and adjustment figure 8.

Figure 8.Categories about evalutaion

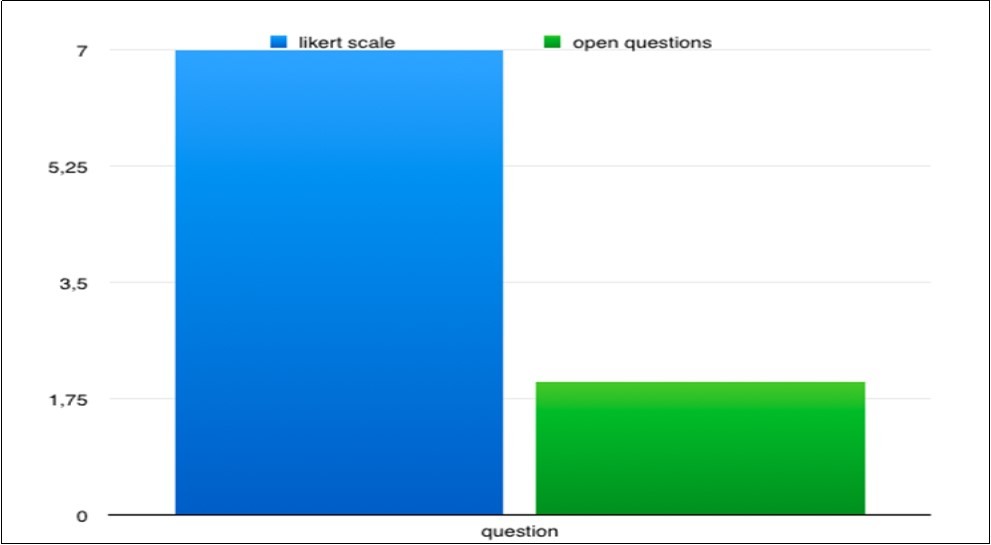

Only 3 instruments take into account opportunities in terms of support given by the environment. The last element of the analysis is the possibility of answering the questions posed by the various evaluation tools. A first form is that of quantitative indicators that, through a Likert scale, provide a score associated with the given answer (from 0 to 4, or from never to always). In other circumstances, the questions are asked to answer with a true or false or with "I am" or "I am not". Finally, there is the possibility to choose between more options, the correct one in the case of knowledge questions, or to identify the one that most represents your opinion.

In addition to quantitative indicators, there are also qualitative indicators. Respondents must describe how they would act in a series of real-life situations or identify the goals that are set in their lives and how to achieve them. The answers are evaluated with a score from 0 (the objectives are not identified) to 3 (they are presented clearly). Other questions ask to tell examples or situations, talk about themselves and their strengths and critical points and describe their convictions and ambitions. Finally, another method used to evaluate self-determination is the completion of stories: the subjects must invent the ending of a story figure 9.

Figure 9.Type of possible answers

The analysis conducted so far highlights some critical issues. The variety of definitions of self-determination is inevitably reflected in the choice of domains and items. For example, the tools that refer to the functional model do not recognize the importance of the environment and fail to take into account the process that leads to self-determination. At the same time the scales based on the ecological model do not consider the individual factors involved in self-determination. The default lenses direct the gaze that, focusing attention on some factors to the detriment of others, can only analyse some aspects but not self-determination in its entirety.

A second critical element is the choice of the recipients of the evaluation. In some cases, the tools collect the opinion of the subjects, while in others they are addressed to family members or teachers. There is then a third case in which the opinions of the subjects with disabilities are integrated or replaced with those of family members and teachers, the partiality of the areas investigated, and of the collected points of view, becomes even more significant considering that self-determination is often used to evaluate programs and projects designed for students with intellectual disabilities. The question remains whether it is possible to study self-determination without considering the opinion of persons with disabilities. And if the opinion of students with intellectual disabilities is important, we need to reflect on the ways of involvement since there are no tools designed for them and the various authors prefer to use the opinion of a third person.

A third element of criticality refers to the role that other people have with respect to self-determination. Above all, the ecological model and the learning model refer to the importance of the environment for self-determination. The other people represent a privileged point of view that currently the various scales exclude.

At this point it may be interesting to ask whether it is not possible to think of a scale that combines the peculiarities of the different tools (attention to individual and environmental factors, recognition of the importance of the process and the impact of self-determination on the lives of the subjects and their family members) and what characteristics this should possess. Starting from the analysis of existing scales, the areas to be investigated could be those described above: autonomy, empowerment, self-realisation, self-regulation, knowledge, skills, opportunities and support. Next, you need to define the indicators, understand how to formulate the questions and how to evaluate the answers. The choice of the indicators, as well as the formulation of the questions, must necessarily take into account the comprehension skills of the subjects with disabilities and the specific features that characterise the individual contexts. For this reason, simplifications can be introduced if they are necessary to help the subjects to understand what is required or to define specific indicators for the peculiarities of the environment.

The scale in relation to the assessment methods, both the use of quantitative and qualitative indicators could be interesting, with different objectives. The former allows a comparison between the points of view of the various subjects and allow us to evaluate how the scores evolve in the various areas over time. Qualitative indicators, on the other hand, favour the collection of situations and episodes, experiences and emotions of people with disabilities but also of family members, teachers and other people involved in the activities. If the quantitative indicators help to define the "how much", the qualitative indicators allow to grasp the "how", giving voice to all those involved in the self-determination pathways. Precisely this qualitative dimension can also help to document the process that leads to self-determination, the strategies used and the significant episodes. The scale, thus conceived, could be used as a tool for comparison between all the subjects involved and can favour the construction of a common and shared language. It is essential to start from the point of view of students with intellectual disability considering their possibilities of understanding and expression of the point of view. Then parents must be involved, who must be at the centre of the life project of the subjects and the objectives linked to self-determination. Finally, it is necessary to gather the opinion of those responsible for specialised services and of the people who interact with the subject (for example teachers and classmates, work colleagues, volunteers and community members).

The scale could be compiled in its complexity or some areas could be selected, based on the objectives of the subjects' life project. The tool would be useful for the verification of existing experiences, to highlight the elements of strength and criticality and, if necessary, introduce changes and changes.

Conclusion

The subject of self-determination is considered one of the main elements for the evaluation of the QOL of students with intellectual disabilities. In the literature there are four models that focus on different aspects: functional, ecological model of learning and of the theory of agency. These models orientate numerous scales that analyse self-determination according to different areas and indicators, both qualitative and quantitative. The scales in some cases are aimed at students with intellectual disabilities, while in others they prefer to collect the opinion of third parties, such as teachers or family members.

Given the partiality of the areas investigated and the points of view collected, it may be interesting to ask whether it is possible to construct a ladder that focuses attention on individual and environmental factors, also taking into account the process and the impact of self-determination on the life of individuals and their families. Analysing the sections present in the various tools identify the following areas: autonomy, knowledge; action/self-regulation; self-realisation; empowerment, opportunities and supports (need for support and opportunities offered). The ladder should collect the point of view of all people participating in self-determination experiences: individuals with disabilities, family members, specialists and people in the community (such as teachers, classmates, work colleagues). With respect to the methods for collecting information, it would be essential to define domains and indicators, but leaving a certain flexibility to be adapted to the characteristics and needs of individuals with disabilities and individual contexts. The indicators could be both quantitative and qualitative, with different objectives both in the evaluation of self-determination and the impact that this has on the life of the subjects. The former would help to define self-determination in numerical terms, allow a comparison between the points of view of the various subjects interviewed and allow the monitoring of scores over time. The qualitative indicators, on the other hand, would emphasize the "how", favouring the collection of the opinions of the various subjects and the report of episodes, experiences and emotions. Qualitative indicators would give the opportunity to describe and document the process of self-determination through the voices of those taking part.

This synthesis represents a first step in the construction of a possible universal scale starting from the analysis of the literature. A comparison would then be necessary with the students with intellectual disabilities, the family members and the other actors involved to understand which domains are really meaningful to them and to build indicators that correspond to the elements that are important to them. In this way we would have a tool capable of combining the point of view of literature with that of the people directly involved. (Table 1)

Table 1. Annex 1 Data extraction sheet| Name and author | sample | items and subscales | domains | mode of response |

| The Arc’s Self-Determination Scale di Wehmeyer & Kelchner, 1995 | students with disabilities, moderate cognitive delay(maximum 15 students) | 72 items in 4 sub scale: care of oneself and one's family; management of interactions with the environment; recreational activities and leisure time management, social and professional activities | Autonomy,empowerment,self regulation,self realization, | Likert scale,completion of stories, division of objectives into smaller passageschoice between two options |

| The Self-Determination Assessment Battery Hoffman et al., 2004 | students with disabilities teachersparents | know yourself,enhance yourself,planning:,action,results of experience and learning | dreams / strengths / weaknesses, needs / preferences, possible options / supports / expectations / decisions / accepting / evaluating / appreciating strengths / recognising rights / responsibilities / taking care of oneself / setting goals / planning actions / forecasting outcomes / being creative / risk / communicate / access resources and supports / negotiate / | Likert Scale (from 0 to 4) |

| Choicemaker Self-Determination Assessment di Martin & Marshall, 1997 | students with moderate disability / emotional / behavioural difficulties although they may be adapted for more severe disabilities | interests,skills,limits,student goals,take the initiative | section 1: decide the objectivesinterests: expressing personal interests / with respect to training / work /skills and limits: expressing limits and personal skills / respect to training / workobjectives: to indicate personal options and objectives / with respect to training / worksection 2: expressing objectives (during the meeting with the students): opening the meeting / presenting the participants / reviewing past goals and performance / asking for feedback / asking questions if you do not understand / manage the diversity of opinions / declare media / close the meeting by summarising the decisionsreporting by students: expressing interests / abilities and limits / options and objectivessection 3: actionstudent plan: divide general goals into specific goals that can be completed now / set standards for specific goals / determine how to receive feedback / determine motivation to complete goals / determine strategies to complete specific objectives / identify priorities and define times / express the belief that goals can be achievedazione degli studenti: riportare le performance/raggiungere gli standard/get feedback on the performance / motivate yourself to complete the objectives / use the strategies to complete the objectives / get the media when it is necessary / follow the programsstudent evaluation: determine if the objectives are achieved / compare the performance to the standards / evaluate the feedback / evaluate the motivations / evaluate the appropriateness of the strategies / evaluate the supports used / evaluate the programs / evaluate the beliefs /adjustments: settle the objectives if necessary / adjust the standards / adjust the methods for obtaining feedback / adjusting the motivation / adjusting the strategies / adjusting the supports / adjusting the programs / adjusting the beliefs with respect to the possibility of achieving the objectives | Likert Scale (from 0 to 4) |

| Self-Determination Scale for College Students (SDSCS) di Chao, 2018 | students with disabilities | 48 items and 4 subscales,autonomy,self,empowerment,autoregulation, | awareness / self-perception, self-understanding / independent life / self-care / locus of control / self-advocacy / understanding of desired results / setting goals / solving problems / adapting behaviours / when I perform a task, I evaluate how the things / dream how my life could be after school ended / think about what I could do better / know what's important to me / plan to explore different options before choosing a career / think about what's good for me when I do something / I like to have goals in my life / I compare my grades with those I expected / ask for directions or I look at the map before going to a new place / I think how well I have done the task / when I want a good grade, I work a lot to get it;I say when I have different opinions or ideas / I tell people when they hurt my feelings / I can make decisions about myself /I can do what I want if I work hard / I can work with others / if I prepare properly I can do the job I want / I can say no to my friends if they ask me to do something that I do not want do / tell people when I think I want to do something that they do not want me to do / I think working hard at school helps to get the job I want / I can try again after a failure / I can make good choices / am able to socialise in new situations / when I need to be able to make decisions that affect me /I'm worried about doing something correctly / it's better to be yourself than to be famous / I think I'm loved because I can love / I'm aware of what I can do well /I accept my limits /I like myself / think I'm important to my family and friends /I think I like other people /I believe in my skills /friends/ | select the statement that best reflects their current situation or opinion with a score ranging from 1 (decidedly disagree) to 5 (decidedly agree) |

| Minnesota Self-Determination Scales: Skills, Attitudes, and Knowledge Scale di Abery e Smith, 2007 | students with disabilitiesparentsteachers | three subscale from 90 items that include:self-determination exercisespreferences in choicesimportance of choices and decisions; | 8 domains.There is also a scale of supports:orientation / skills and knowledge /application of skills / training / quality of training /supervision / work habits of staff / skills related to self-determination / attitudes and beliefs related to self-determination /knowledge that supports self-determination | students are asked to respond with: completely disagree / disagree / agreement / completely in agreement.Educators and parents are asked to respond in a similar way (rarely, little, not very often, often, very often, always) |

| ARC-INICO Self-Determination Assessment Scale di Verdugo et al., 2009 | students with disabilities | 48 item 4 subscales with 97 items:autonomy,empowerment, self-realisation,self-regulation | I prepare meals myself / I take care of my clothes / I take care of the housework,I keep my things in order,if I have an accident I know how to solve it, I take care of my image and personal hygiene,I can use public transport,I can order at a bar,I arrive in time to an appointment and I tell where I was with my friends,I'm involved in activities that I like,I participate in the activities proposed by the school,I write messages and I talk on the phone with friends and relatives,I listen to the music I like,I have the chance to go to concerts or to the cinema,I make plans for my future,I carry out activities related to my interests,I work (or worked) to make money,I ask people to visit their workplace if I'm interested,I choose clothes and objects I use every day,I choose my hair style,I choose gifts for my friends and family,I choose how to furnish my room,I organise free time based on the activities I like,I work to increase my career chances,I choose how to spend my money; | 4-point Likert scale |

| Peper Transition Planning Scale di Peper, 2009 | students with disability | 100 itemsSkills,knowledge ,/ attitudes / beliefs | Definition of objectives / if I had to explain what a transition plan is to a person who does not know it, how would you explain it / What are the areas involved in a transition project / What are the objectives of a transition project in the sphere of work , training and participation in community life, free time and one's daily life / What are the objectives of your personalised project?decision making process / tell me two examples of decisions you made during the school day and outside the school environment / describe how the team working on your project makes the decisions / Which goals have been suggested by you / Who takes most of the decisions that affect your life /problem solving / tell me about a problem you had to solve. If you succeeded like you did? If you failed because? You could have done differently / What are the six steps to solve a problem?self-awareness what is the name of your disability / what are three effects of disability on your daily life / What are three strategies you use at home, at school or in your job to be more successful / Tell me three strategies that others use to help you achieve your goals /communication / show me two examples of passive / aggressive behaviour /explain to me two reasons why assertive behaviour is to be preferred over passive or aggressive / show me three examples of non-verbal communication /Laws, rights, responsibilities / at what age the subjects are invited to their meeting for the personalised project / To which age the project ends / Tell me three civil rights related to your disability / Describe two places you went or two people you have spoken that violated your rights / knowledge of available resources /nominate a resource that will be available when your project is finished / describe how you will have access to resources if you need them / describe which services related to work guaranteed by the state you will have available / Describe the services that the social service can provide layout/self-knowledge / describe two points of strength and two elements of difficulty / tells two personal interests and two values / attitudes and beliefs / tell me two ways to achieve your goals / tell me examples of two things you tried to do / tell me about four challenges that you are facing at school or at home / tell me about your progress with respect to two of your project's goals this year / provide an example of how you could achieve your goals starting from yourself / tell me where you would be both to live and to work in five years /locus of control / do you believe you will reach your goals? Why / Do you believe that you can get the diploma? Why / Will you reach the goals that are important to you? Why / Do you believe that your efforts will have a relapse on your future? Why/self-esteem and self-concept /give an example of a goal achieved in the past so you are proud of yourself / describe an example of a goal you failed to achieve in the past and explain why / Do you think the team is supporting you in your personal project? Why / Have you accepted your disability? Why | open questionsexamplesdescriptions |

| ADIA Cottini | teachersparents | perceptions and knowledge,skills,opportunity,supports, | knows their strengths / expresses desire to do activities or know things / knows that some things are fixed by the organisation / distinguishes a current situation from a future / understands the effects of their actions /knows how to express wishes / knows how to make choices / knows how to plan objectives / knows how to evaluate the effects of your actions / self-correcting when checking the ineffectiveness of a strategy /the context offers the possibility of manifesting desires / the context offers the possibility of making choices / the context offers the possibility of planning objectives / the context offers the possibility of evaluating the effects of one's actions / the context offers the possibility to self-correct when checking the ineffectiveness of a strategy /how much support is needed to adopt behaviours that go in the direction of satisfying the objectives / How much support is needed to understand the dialectic between hetero-determined and self-determined activities and behaving accordingly / How much support is needed to self-regulate one's behaviour / How much support is needed? propose to others their own choices and plans / How much support is needed to be able to self-determine | Likert Scale |

| Self-‐Determination Inventory: Self-‐Report (SDI:SR) Shogren et al. 2014 | students with or without disability/teachers/parents | voluntary actionconcrete actionsbeliefs of control of the action | I have what I need to achieve my goals / I think there is more than one way to solve problems / I consider many possibilities when I plan my future / I know what I can do well / I plan the weekend activities I like / I keep trying even after a failure / I set my goals / I think working hard helps achieve the goals / I choose the activities I want to do / work hard to achieve my goals / I understand the ways to get around obstacles / I trust the my skills / my past experiences help me to plan what I will do next / I think about each of my goals / I make choices that are important to me / I look for new experiences that I think I will like / I can concentrate to achieve my goals / I choose the furnishings of my room / I act when new opportunities arise / I know my strengths / use different ways to achieve my goals. | declare to be in agreement or not with the statements |

References

- 1.M A Verdugo, Navas P, L E Gómez, R L Schalock. (2012) The concept of quality of life and its role in enhancing human rights in the field of intellectual disability. , Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 56(11), 1036-1045.

- 2.Algozzine B, Browder D, Karvonen M, D W Test, Wood W M. (2001) Effects of interventions to promote self-determination for individuals with disabilities. , Review of Educational Research 71(2), 19-277.

- 3.Lachapelle Y, M L Wehmeyer, M C Haelewyck, Courbois Y, KeithK D et al. (2005) The relationship between quality of life and self‐determination: an international study. , Journal of intellectual disability research 49(10), 40-744.

- 4.Mumbardó-Adam C, Guàrdia-Olmos J, Giné C, S K Raley, K A Shogren. (2018) The Spanish version of the Self-Determination Inventory Student Report: application of item response theory to self‐determination measurement. , Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 62(4), 303-311.

- 5.Ahmad W, A T Thressiakutty. (2018) Effect of teacher's training on enhancing self-determination among individuals with intellectual disability. , Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry 34(1), 16.

- 6.E W Carter, K L Lane, Cooney M, Weir K, C K Moss et al. (2013) Parent assessments of self-determination importance and performance for students with autism or intellectual disability. , American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 118(1), 16-31.

- 7.J L Luckner, A M Sebald. (2013) Promoting self-determination of students who are deaf or hard of hearing. , American annals of the deaf 158(3), 377-386.

- 8.Frielink N, Schuengel C, P J Embregts. (2018) Autonomy support, need satisfaction, and motivation for support among adults with intellectual disability: Testing a self-determination theory model. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities. 123(1), 33-49.

- 9.M L Wehmeyer. (2005) Self-determination and individuals with severe disabilities: Re-examining meanings and misinterpretations. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 30(3), 113-12.

- 10.M L Wehmeyer, S B Palmer, Shogren K, Williams-Diehm K, J H Soukup. (2013) Establishing a causal relationship between intervention to promote self-determination and enhanced student self-determination. , The Journal of Special Education 46(4), 195-210.

- 11.K A Shogren, M L Wehmeyer, T D Little, A J Forber-Pratt, S B Palmer et al. (2017) Preliminary validity and reliability of scores on the Self-Determination Inventory: Student Report version. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals. 40(2), 92-103.

- 12.R J Stancliffe. (2001) Living with support in the community: Predictors of choice and self-determination. , Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 7(2), 91-98.

- 13.M L Wehmeyer, Bolding N. (2001) Enhanced self‐determination of adults with intellectual disability as an outcome of moving to community‐based work or living environments. , Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 45(5), 371-383.

- 15.B H Abery, R J Stancliffe. (2003) An Ecological Theory Of Self-Determination: Theoretical. Theory in self-determination: Foundations for educational practice. 25.

- 16.D K Mithaug, Agran M, J E Martin, M L Wehmeyer. (2002) Self-determined learning theory: Construction, verification, and evaluation.Routledge.

- 17.Wolman C, C S Mccrink, S F Rodríguez, Harris-Looby J. (2004) The accommodation of university students with disabilities inventory (AUSDI): Assessing American and Mexican faculty attitudes toward students with disabilities. , Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 3(3), 284-295.

- 18.GetzelE E, C A Thoma. (2008) Experiences of college students with disabilities and the importance of self-determination in higher education settings. Career development for exceptional individuals. 31(2), 77-84.

- 19.K A Shogren, M L Wehmeyer, S B Palmer, Forber-Pratt A, T J Little et al. (2014) Self-Determination Inventory: Self-Report [Pilot Version]. Lawrence, KS:Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities.

- 20.E W Carter, K L Lane, Cooney M, Weir K, C K Moss et al. (2013) Parent assessments of self-determination importance and performance for students with autism or intellectual disability. , American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 118(1), 16-31.

- 21.M L Wehmeyer. (2015) Framing the future: Self-determination. , Remedial and Special Education 36(1), 20-23.

- 22.Y C Chou, M L Wehmeyer, S B Palmer, Lee J. (2017) Comparisons of self-determination among students with autism, intellectual disability, and learning disabilities: A multivariate analysis. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 32(2), 124-132.

- 23.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A et al. (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P). 4(1), 1.

- 25.Hoffman A, Field S, Sawilowsky S. (2004) Self - Determination Assessment Battery. User’s guide. Center for Self-Determination and Transition: Promoting Resiliency and Well-being Throughout the Lifespan. College of Education,Wayne State University.

- 26.J E Martin, L H Marshall. (1997) ChoiceMaker self-determination assessment. , Longmont, CO:Sopris West

- 27.P C Chao. (2018) Using Self-Determination of Senior College Students with Disabilities to Predict Their Quality of Life One Year after Graduation. , European Journal of Educational Research 7(1), 1-8.

- 28.Wolman C, C S Mc, S F Rodríguez, Harris-Looby J. (2004) The accommodation of university students with disabilities inventory (AUSDI): Assessing American and Mexican faculty attitudes toward students with disabilities. , Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 3(3), 284-295.

- 29.B H Abery, Smith J, Elkin S, Springborg H, Stancliffe R. (2007) The Minnesota Self-Determination Scales-Revised: Skills, Attitudes, and Knowledge Scale.

- 30.M A Verdugo, Martín-Ingelmo R, Jordán de Urríes, B F, Vicent C et al. (2009) Impact on quality of life and self-determination of a national program for increasing supported employment in Europe. , Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 31(1), 55-64.

- 31.C R Peper. (2009) Examining the reliability and validity of a self-determination assessment for transition planning.

Cited by (1)

- 1.Lifshitz Hefziba, 2020, , , (), 253, 10.1007/978-3-030-38352-7_7