Insect-Based Foods: A Comprehensive Review on Nutritional Benefits and Environmental Sustainability

Abstract

The growing population demands and environmental concerns associated with traditional protein sources have prompted the exploration of alternative and sustainable food sources. The purpose of this comprehensive review is to highlight the nutritional benefits and sustainability of insect-based foods as a promising solution. Global population growth necessitates innovative approaches to meet the demand for nutritious and sustainable protein sources. There are numerous challenges associated with traditional livestock farming, including land use inefficiency, high water usage, and greenhouse gas emissions. As a result, edible insects have emerged as a viable alternative, providing proteins (35-77% of dry matter), healthy fats (10-50%), essential amino acids, and micronutrients such as iron (up to 31mg/100g) and zinc (up to 20mg/100g), vitamins, and minerals. In contrast to livestock, which requires 22,000-43,000 liters of water to produce 1 kg of beef, insect farming consumes significantly less water and land resources. Insects have the potential to address nutritional deficiencies and strengthen food security as they are recognized for sustainable production. The study thoroughly investigates the literature addressing environmental and sustainability concerns associated with edible insect farming, using a rigorous bibliometric and scientometric analysis via Vos viewer. With the help of Vos Viewer, it was possible to identify the geographical distribution of countries that contributed to the field of edible insects and their acceptance, as well as the top ten documents in this field with the most citations and mostly used keywords in this field of research. Future research and implementation strategies will be able to benefit global food security and environmental conservation through these alternative protein sources.

Author Contributions

Copyright © 2025 Anvy S Isaac, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

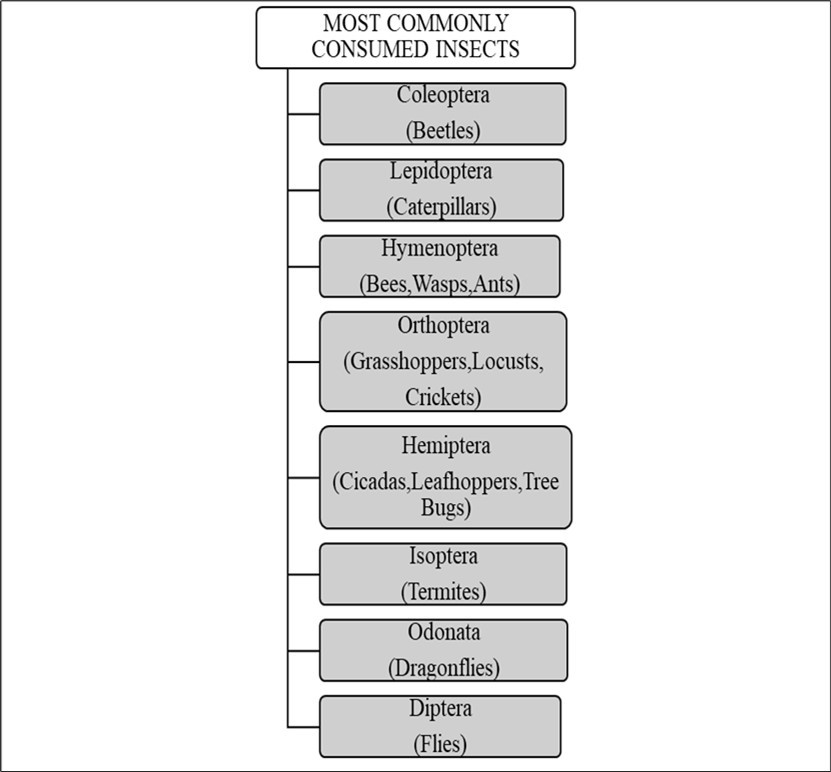

Why are insects considered food when we have so many traditional options? Although this question may appear unusual at first glance, it is critical in today's world, where sustainable decisions will shape our future. Entomophagy is simply eating insects.1 The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations predicts that by 2050, the world population will reach nine billion, necessitating a significant increase in food production. The population is also expected to reach eight billion in 2024, a 0.88% increase from 2022.This rapid growth increases pressure on global food systems, necessitating a rethinking of agricultural practices. Godfray et al.2 emphasized the importance of increasing food production in a sustainable manner to meet the demands of a rapidly growing population. The demand for more diverse and nutrient-dense diets is already posing challenges for traditional farming systems, particularly as urbanization increases.The growing demand for protein-rich foods has serious consequences, making it critical to find new solutions that ensure food security and proper nutrition. Traditional protein sources, which are mostly derived from animals, face issues such as environmental damage and a limited ability to expand production. Tilman and Clark3 explained that traditional agriculture is constantly under pressure to produce enough food while minimizing its negative impact on the environment. With these challenges in mind, this review looks at insect-based foods as a practical solution that can provide good nutrition while also contributing to environmental sustainability. People have eaten insects throughout history, and the practice remains widespread and legal in many parts of the world today. Communities in Australia, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa eat a wide range of insects. Insects are a more cost-effective and environmentally friendly source of protein than traditional livestock because they require far less land and water. Edible insects contain essential amino acids, vitamins, and minerals. Rumpold and Schluter4 discovered that certain insect species are particularly high in protein and healthy fats, making them a nutrient-dense option for human diets. Their diverse nutritional content can help combat malnutrition and improve food security. According to estimates, insects provide 9.96 to 35.2 g of protein per 100 g, indicating a high potential to replace traditional animal protein sources.5 In addition, insects provide ten essential and semi-essential amino acids required for human health. Crickets (Brachytrupes membranaceus Drury), grasshoppers (Zonocerus variegatus Linnaeus), termites (Macrotermes species), silkworms (Anaphe venata Butler), palm yam beetles (Heteroligus meles Billb), bees (Apis mellifera Linnaeus), and weevils (Rhynchophorus phoenicis Fabricius) are among the most commonly consumed insects.6 Eating insects is widely accepted in African and Asian cuisines. However, in Western countries, many people find insect consumption unpleasant or disgusting and thus avoid it as part of their diet.7 Limited awareness and understanding of food safety in insect-based products8 may further impede their acceptance and integration into mainstream diets. Most countries still limit the introduction9 and promotion of insects in human diets. Even though entomophagy has numerous benefits, consumer acceptance remains one of the most significant barriers to the widespread adoption of edible insects. Because insects have never been a major part of everyday meals, many people are hesitant to consider them a source of nutrition. The primary reason for this rejection is a sense of disgust. In South Asia, social acceptance is particularly low, and little is known about the benefits of insect-based products. The main reason for opposition is people's general dislike of these products, and the fact that they are unfamiliar makes acceptance even more difficult.10, Figure 1.

Figure 1.List of commonly consumed insect orders11

Nutritional Composition

In recent years, there has been a lot of interest in the nutritional profiles of various edible insect species as a source of protein that is both sustainable and alternative to traditional livestock. Among the many edible insects studied, mealworms (Tenebrio molitor), crickets (Acheta domesticus), grasshoppers, termites, silkworms, and other insects have the potential to provide nutrition to humans. To gain important insights into the potential role of these insects in addressing global food security challenges, researchers have attempted to thoroughly analyse their nutritional profiles. The nutritional composition of 236 edible insects has been published by the Food and Agriculture Organization, 2021. Arsenura armida, an edible insect, was incorporated into both non-defatted (NDF) and defatted flour (DF) to assess the nutritional profile, physical characteristics, and technological functions. It was discovered that NDF comprises 24.18 percent of lipids. The protein content of the flours was high, 20.36% in NDF and 46.89% in DF. The calculated molecular weight of the present soluble protein ranged from 12 to 94 kDa. Arsenura armida proved to be a good alternative to animal protein due to their functional and physical properties.12 The Brazilian super worm Zophobas morio and the Jamaican field cricket Gryllus assimilis were discovered to contain 65.52% proteins, 21.80% lipids, 8.6% carbohydrates, 408% ashes, 40.64% lipids, 8.17% ashes, and 1.39% carbohydrates, respectively.

As per a study conducted in Nigeria, insects with high crude fat, protein, and vitamin content included Zonocercus variegatus, Macrotermes bellicosus, and Cirina forda. In comparison to the other two insects, Z. variegatus had higher concentrations of all necessary minerals except Na, K, and Fe. The study found that the three edible insects have adequate nutritional value, making them a viable substitute for other foods in the fight against nutritional deficiencies caused by malnutrition. Furthermore, the functional characteristics of these insects suggest that the food industry could use them to fortify and enrich human and animal diets.13 A study was conducted to know the effects of adding insect flour to bread on texture, color, dough rheology, chemical composition, and nutritional value. The fat percentage in insect flours varied from 8.37% to 29.64%, the protein content from 49.89% to 62.51%, and the total dietary fibre from 7.75% to 9.48%. Compared to wheat bread, 10% insect flour increased protein content and lysine amino acid levels significantly. Various insect species have different fatty acid profiles, with oleic, palmitic, and linoleic acids having high concentrations.

Cricket (Acheta domesticus)

Acheta domesticus, commonly known as house cricket, is an edible insect with a high protein and nutrient content. It has the potential to be used in the food industry as it is safe, environmentally sustainable, and has a higher biological value. It is highly digestible and contains many fatty acids, including palmitic, stearic, oleic, and linoleic. Many traditional foods are deficient in vitamin B complex, necessitating the use of supplements, whereas house crickets are high in vitamin B complex. In general, house crickets are safe to eat and make cultivation effortless. They have the potential to be used in processed foods due to their solubility and ability to hold water and form gels and emulsions. Furthermore, incorporating its flour into products can boost nutritional value and represent a promising industry. For production, 92% of insects are gathered from the wild, whilst only a small amount is collected through international breeding.14 Acheta domesticus is regarded as a manageable species that can be reared domestically using low-cost farming techniques.15, 16 As the consumption of edible insects grows globally, food organizations must ensure their safety and lack of health risks.

In addition to eggs, shellfish, peanuts, and milk, insects also have the potential to cause allergic reactions. Every year, allergic reactions have been reported in China, where insects are commonly consumed. People with crustacean allergies are also susceptible to allergenicity in cricket-based products. As a result, shrimp-specific IgE levels can be used to reduce the risk of cricket consumption among allergic customers.17 Aside from antibodies, insect proteolysis or microwave heating during processing can produce hypoallergenic cricket protein ingredients or products.18

House crickets are high in protein, with dry weights ranging from 48.06 to 76.19g per 100g. They are high in micronutrients such as calcium, potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, sodium, iron, zinc, manganese, and copper. Not only minerals but also rich in vitamins like riboflavin, pantothenic acid, biotin, and folate which are usually the most deficient nutrients in humans.17 According to the National Institute of Health, the daily reference intake for children aged 4 to 8 is 19g/day, while for men and women over the age of 19 is 56 and 46g/day, respectively, which can be obtained by 100g of house cricket dry matter. The carbohydrate content ranges from 1.6 to 10.2g, while the fibre content ranges from 3.9 to 7.5 g/100 g DW.19 Chitin is the primary component that contributes to the high fibre content. Previously, the digestion of chitin in humans was questioned, but recently chitinases were discovered in human tissues, which could aid in the prevention of parasitic infections and allergic conditions.17, Table 1

Table 1. Nutritional composition of Acheta domesticus17| NUTRITIONAL FACTS Proximates | Values (g/100g) |

| Protein | 48.06 - 76.19 |

| Carbohydrate | 1.6 - 10.2 |

| Fiber | 3.9 - 7.5 |

| Energy(kcal) | 147.0 - 455.50 |

| Total fat content | 3.30 - 43.90 |

| Vitamins | Values (mg/100g) |

|---|---|

| Riboflavin (B2) | 0.95 - 11.07 |

| Pantothenic Acid (B5) | 2.30 – 7.47 |

| Biotin (B7) | 5.00 – 55.19 |

| Folate (B9) | 0.15 – 0.49 |

| Retinol | 24.33 |

| Thiamine (B1) | 0.02 - 0.13 |

| Pyridoxine (B6) | 0.13 - 0.23 |

| Vitamin C | 9.74 |

| Niacin (B3) | 0.36 - 12.59 |

| Minerals | Values (mg/100g) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 27.50 - 210.00 |

| Potassium (K) | 347.00 - 1211.10 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 0.89 - 4.40 |

| Phosphorus (P) | 225.00 - 1038.90 |

| Sodium (Na) | 101.44 - 471.4 |

| Iron (Fe) | 1.93 - 11.23 |

| Zinc (Zn) | 6.71 - 22.20 |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.89 - 4.40 |

| Copper (Cu) | 0.51 - 4.86 |

Black Field Cricket (Gryllus assimilis)

Gryllus assimilis, also known as black field cricket, is another insect that is regarded as a promising alternative to conventional proteins.20 Studies have been conducted to assess the chemical and nutritional composition of this insect, and they show that they contribute as a substitute source of energy and protein.21, 22 Furthermore, it demonstrated that incorporating insect powder into products would result in higher protein quality. It was high in protein (57.36% to 67.97%), phosphorus (512.00-732 mg/100 g), copper (1.45-3.01 mg/100 g), iron (5.41-8.41 mg/100 g), zinc (11.62-25.57 mg/100 g), manganese (1.63-8.08 mg/100 g), magnesium (84.00-180.00 mg/100 g), and potassium (624.00-820.00 mg/100 g). Niacin levels range from 1.88 to 3.21 mg per 100 g. The proteins had high digestibility (84.48-92.53%) and increased solubility in alkaline pH nearly equal to 11 and lysine was identified as the limiting amino acid. The insect development stage influences nutritional content, amino acid profile, and functional protein properties.20, Table 2

Table 2. Nutritional composition of Gryllus assimilis20| NUTRITIONAL FACTS | Values (mg per 100g) |

|---|---|

| Protein | 57.36 – 67.97g |

| Phosphorus | 512.00 – 732 |

| Copper | 1.45 – 3.01 |

| Iron | 5.41 – 8.41 |

| Zinc | 11.62 – 25.57 |

| Manganese | 1.63 – 8.08 |

| Magnesium | 84.00 – 180.00 |

| Potassium | 624.00 – 820.00 |

| Niacin | 1.88 – 3.21 |

Dragonflies (Odonata)

Dragonflies are a staple in the diets of many ethnic communities worldwide.23 They are of two types: Pantala sp. and Sympetrum sp. Dragonflies have a higher protein content than traditional livestock, ranging from 45% to 76%.24 Additionally, 80% of insect lipids contain essential fatty acids.25 Chitin, a component of dragonfly exoskeletons, improves the immune system and provides strong resistance to parasite diseases.26, 27 They contain a variety of amino acids, including isoleucine, valine, and leucine. Dragonflies can help with vitamin C deficiency because they contain vitamin C, thiamine, riboflavin, pantothenic acid, niacin, pyridoxine, and vitamin B12.28 In contrast to meat, dragonflies have a higher mineral content than meat. Insect edibles are an excellent solution to malnutrition or for people who do not have the resources to purchase supplements. Insects are not only edible but also medicinal, with antibacterial, immunological, analgesic, and anti-rheumatic properties.29 In dried form, they can be used to treat colitis, cough, malaria, skin allergies, boils, blood pressure, and so on 28, Table 3.

Table 3. Nutritional composition of Dragonflies28| NUTRITIONAL FACTS | Values (%) |

|---|---|

| Protein | 54.24 |

| Fat | 16.72 |

| Ash | 12.85 |

| Fibre | 9.96 |

| Total Carbohydrate | 6.23 |

| Lysine | 8.37 |

| Histidine | 6.93 |

| Methionine | 4.07% |

| Minerals & Vitamins | Values (mg/kg) |

| Vitamin C | 30 |

| Vitamin B2 | 34.1 |

| Vitamin B3 | 38.4 |

| Vitamin B5 | 23 |

| Vitamin B12 | 54 |

| Calcium | 124.96 |

| Magnesium | 116.9 |

| Potassium | 1591.9 |

| Sodium | 1339.76 |

| Iron | 158.210 |

| Manganese | 6.790 |

| Copper | 4.180 |

| Zinc | 74.77 |

| Selenium | 0.193 |

Grasshoppers (Ruspolia nitidula)

A study on the nutritional and commercial potential of edible grasshoppers was conducted in Uganda and many East African tribes. They were found to be high in protein, with 36-40%, 4-6mg/kg potassium and phosphorus. The biological value and digestibility have not yet been determined, and further research is underway. The product's overall acceptability was 6.7-7.2 on a 9-point hedonic scale, indicating that it is the flavour, appearance, and aroma that entice people to consume rather than the raw material.30, Table 4

Table 4. Nutritional composition of Grasshoppers30| Nutritional composition | Values |

|---|---|

| Protein | 36 – 40% |

| Fat | 41 – 43% |

| Carbohydrate | 2.5 – 3.2% |

| Ash | 2.6 – 3.9% |

| Dietary Fiber | 11.0 – 14.5% |

Traditional Preparation methods

| Insect | Stage Consumed | Preparation Method |

| Alcaerrhynchus grandis | Adult | Fried or boiled with vegetables |

| Antilochus coqueberti | Adult | Fried or boiled with vegetables |

| Aspongopus nepalensis | Adult | Abdomen is removed and is prepared into chutney |

| Allomyrinadichotoma | Adult | Appendages discarded, boiled, steamed or roasted |

| Anomala sp. | Adult | Roasted or boiled |

| Aristobia sp.. | Adult | Dewinged, roasted, or boiled & smoked |

| Batocera roylei | Larvae, Adult | Dewinged, smoked, roasted or boiled |

| Catharisus sp. | Adult | Wet paste made after discarding the body cover |

| Cyclochila virens | Adult | Dewinged, roasted |

| Dorcus sp. | Larvae, Adult | Roasted, boiled, paste, antennae and appendages are also removed |

| Lepidiota sp. | Adult | Boiled or Smoked |

| Monochamus versteegi | Adult | Dewinged, smoked, roasted and boiled |

| Odontotaenius sp. | Larvae, Adult | Dewinged, roasted, smoked, boiled or fried |

| Odontolabis gazella | Larvae, Adult | Larvae is fried in oil, and is then boiled with vegetables before consumption, adults are roasted |

| Oplatocera sp. | Adult | Wings and appendages are discarded, smoked, and boiled |

| Grasshoppers | Adult | Wings, legs, and stomach are removed, washed with water, and then roasted or cooked using vegetable oil, chilli, ginger, garlic. |

| Odonata | Larvae | Boiled or roasted |

| Vespa sp. | Adults | Dewinged, fried or consumed fresh |

| Apis cerana | Adult | Wings and antennae are discarded, roasted, or is consumed in paste |

| Red Ant | Whole | Eaten with rice or used as a snack |

| Pycna repandar | Adult | Dewinged, roasted or as paste |

| Propomacrus sp. | Adult | Dewinged, smoked, roasted or boiled |

| Prosopocoilus sp. | Larvae | Antennae and appendages are discarded |

| Sternocera sp. | Adult | Boiled or smoked |

| Trictenotoma sp. | Adult | Dewinged, smoked or boiled |

| Xylorhiza sp. | Larvae | Boiled and fried |

| Eumenes sp. | Larvae | Eaten directly or is made into a paste |

| Vespa sp. | Adult | Fried or fresh after removing the wings |

| Polistes sp. | Adult | Dewinged, larvae is smoked with bee hive |

In addition to their high nutritional value, several other factors must be considered. One significant challenge is cultural and social acceptance. While entomophagy is widespread in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, it is less popular in Western countries, where insects are often associated with disgust, fear, or filth. This negative perception remains a significant barrier to incorporating insect-based foods into mainstream diets. There are also limitations to current research. Most nutritional research focuses on a few commonly consumed insects, such as crickets, grasshoppers, and mealworms, while thousands of edible species go unexplored. Nutrient values also differ greatly depending on species, rearing conditions, and feed, making it difficult to generalize findings Table 5.

Processing methods have a significant impact on the nutritional quality and shelf life of insect products.

For example, freeze-drying preserves proteins and heat-sensitive vitamins, whereas roasting or oven-drying may result in nutrient loss but improve taste and storage stability. Fermentation and grinding into powders improve digestibility and ease of use in foods, but they may shorten shelf life. A direct comparison with traditional animal proteins emphasizes the benefits of insects. Fresh beef and chicken provide 26-27% protein, while fish provides 20%. In contrast, edible insects can have 35-77% protein by dry weight, with crickets and grasshoppers reaching 60-70%. They are also higher in micronutrients, with iron levels reaching 31 mg/100 g and zinc levels reaching 20 mg/100 g, which are often higher than those found in beef or chicken. These traits make insects a promising and sustainable alternative.

Environmental Sustainability

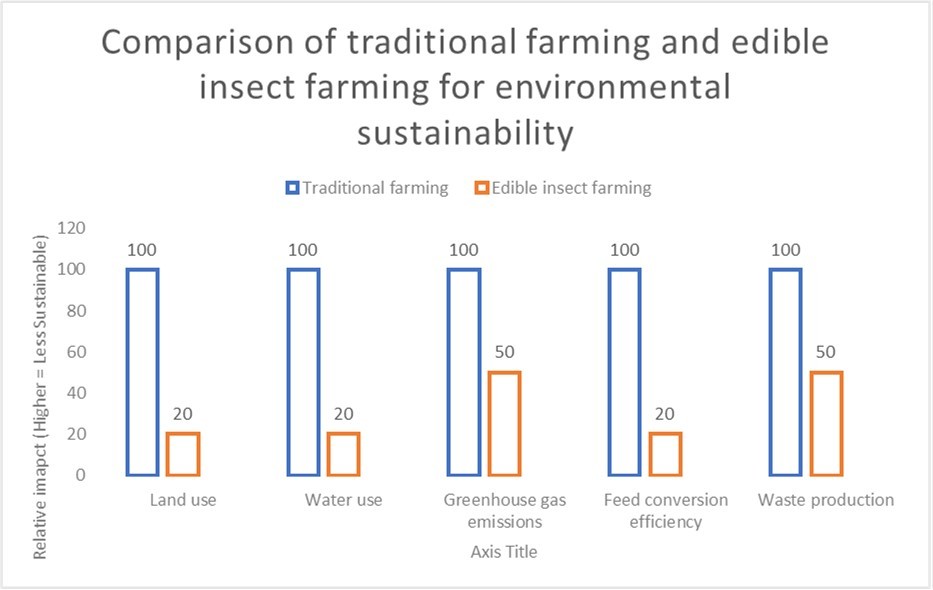

Climate has a major impact on agricultural practices and the overall productivity.32 It influences both traditional farming as well as insect farming. It also has a major influence on which crops and livestock are appropriate for a given area in traditional farming. Temperature, precipitation, and seasonal variations can have an impact on crop yields and livestock forage availability. Severe weather conditions, like floods or droughts, put traditional farming systems at serious risk and affect livelihoods and food production. These difficulties are made worse by climate change, which adds unpredictability and may change the geographic distribution of pests and crops. Agriculture has been one of the primary causes of climate change, accounting for about 18% of global greenhouse gas emissions.33, 34 Since edible insects appear to be a more sustainable and environmentally friendly source of nutrients than any other farming as they require less land, water, and manpower, they are capable of providing benefits to the economy and environment.35 To feed the world’s growing population, food production has to considerably rise.36 Resources like energy, water, land, and ocean get used up more in the case of traditional farming. Usage of insecticides, and pesticides would dramatically rise. If food production continues in its current manner, deforestation, and environmental degradation is expected. Particularly since livestock production makes up about 70% of all agricultural land used worldwide for food and fodder, it would worsen the environmental issues.36 More feed and cropland will be needed for increased animal production, which could result in more deforestation. It’s not advocating that human should solely rely on insects for sustenance, besides some edible insects can be regarded as regular foods and introduced into society as it has their nutritional benefits and help to prevent hunger and preserve the sustainability of the environment Figure 2.

Figure 2.The bar graph depicts a comparison of traditional farming and edible insect farming35

The ratio of feed to meat

According to research, crickets require less than 2kg of feed for every kg of body weight increase.37 Conversely, 2.5kg of feed is required for chicken, pork, and up to 10 kg of beef in order to produce a 1kg increase in body weight.38 As a result, crickets ' feed-to-meat ratio is roughly twice as high as that of chickens and four to twelve times higher for pigs and cattle.

Chemical-free solutions.

When compared to traditional livestock, insects are raised on organic side streams using various biological waste, manure, compost, and human waste, reducing environmental contamination.39 In contrast, traditional livestock uses pesticides, insecticides, and pest repellents, which can pollute the environment and ecosystem. They can also harm soil fertility in the long run.36

Carbon Footprint Solutions

Insects emit fewer gases and ammonia than pigs and cattle. Livestock rearing would emit 18% of greenhouse gases. They emit large amounts of methane and nitrous oxide, which contribute significantly to global warming. However, farming of insects such as crickets, locusts, and mealworm larvae produces less than cattle and pigs. Livestock waste, including manure urine, which contains ammonia, contributes to environmental pollution by causing nitrification and soil acidification.36

Usage of Water

Insect farming uses less land and water than cattle rearing. By 2025, an estimated 1.8 billion people will live in water-scarce regions. Water scarcity poses a global threat to biodiversity, agriculture, and food production. Agriculture consumes roughly 70% of the world's freshwater.40 Meat production requires significant amounts of water. Estimated water requirements for producing 1 kg of meat are 2300 L for chicken, 3500 L for pork, and 22 000-43 000 L for beef.41 Estimates of the amount of water required to produce 1 kg of edible insects are unknown but are thought to be significantly lower.36, Table 6

Table 6. Comparison of traditional farming and edible insect farming35| Factors | Traditional Farming | Edible Insect Farming |

| Land use | High | Low |

| Water requirement | High | Low |

| Greenhouse gas emission | High | Low |

| Feed conversion efficiency | Low | High |

| Waste production | High | Minimal waste |

| Risks to humans, animal, plants and biodiversity | Risks are seen | Must be carefully evaluated |

| Changes in habitat and wildlife impacts | Significant | Minimal if properly managed |

| Use of chemicals | High | Biological waste |

Industrial Processing Methods

Before consumption, insects must go through certain stages that make them more convenient for people to eat. Some people prefer not to eat insects as they are, so they are grounded into granular or paste forms that can be added to other products as a fortifier. Steaming, boiling, baking, deep-frying, sun-drying, and smoking are the steps involved.42 In some tropical countries, insects are eaten as a whole, but allergens pose a challenge. As a result, certain body parts, such as wings and legs, are removed.43 According to research, newly developed products such as patties, pasta, and bread are more appealing to consumers because insects are invisible to their eyes. Insects are further utilized in fish and poultry feed. Maggots, or housefly larvae (Musca domestica), are widely used in Nigeria, Cameroon, Russia, South Korea, and Togo. The use of maggots reduces the need for harmful pesticides in poultry farming. Cricket is the most commonly used pet food. Insects are not popular in dog food, but they are fed to cats.44 As a result of allergens, traditional processing methods are no longer considered adequate to meet market demands, therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the technologies. The food chain begins with insect harvesting and ends with the consumer consuming the product on his or her plate. Pre-treatments, drying, and extraction are some of the processing methods. Pretreatment methods can be classified again, such as blanching, which effectively reduces moisture, retains high ash content, asphyxiation, carbon dioxide plus blanching methods, and freezing. Blanching and the carbon dioxide plus blanching method were recommended as the best procedures for preserving insect quality and nutritional composition. The processing technologies used for different insects vary.45 After pretreatment, the next step is drying to extend the shelf life. It includes both traditional methods like sun-drying and oven-drying, as well as modern methods like freeze drying and microwave drying. Drying would reduce moisture content, preventing microorganism growth.46 Solar and oven drying are commonly used to process whole insect bodies, whereas freeze drying, microwave drying, and some novel drying technologies are primarily used to manufacture insect flour and powders. For commercial industrial production, freeze-drying is the most common method for drying edible insects. It allows for continuous dehydration of frozen insects via sublimation without causing significant physical changes or colour loss. Furthermore, freezing methods appear to have less impact on food flavour, aroma, and nutritional value. Microwave drying is an electromagnetic wave-based technology. Compared to traditional hot air drying, microwave drying produces product quality comparable to freeze-drying, with generally improved aroma and nutritional value. On top of that, microwave drying has a short processing time and produces a product with good microbial stability. One of the disadvantages of microwave drying is uneven heating, which can cause physical damage to the product.44, Table 7

Table 7. Processing methods of edible insects4544| Methods | Types |

|---|---|

| Pre-treatments | Freezing ( -20℃) |

| Blanching (insects are immersed in boiling water for 40seconds) | |

| Asphyxiation (deprived oxygen which results in death or unconsciousness) | |

| Blending (insects are blended for 2min by a homogenizer) | |

| Carbon dioxide treatment (Insects are filled in a plastic container filled with carbon dioxide for 120hrs) | |

| Carbon dioxide plus blanching (insects are treated with carbon dioxidefor 10min before blanching) | |

| Drying | Solar drying (reduced vitamins) |

| Freeze drying (increased amino acids) | |

| Oven drying (increased mineral content such as potassium, phosphorus,zinc and magnesium) | |

| Solar drying (increases oleic acid)Smoke drying (lipid preservation) | |

| Cold atmospheric pressure plasma (causes pH reduction on surfaces)High pressure hydrostatic technology | |

| Extraction | Chemical extraction (chitin extraction) |

| Sonication assisted extractionAlkaline extraction (protein extraction)Defatting | |

| Supercritical carbon dioxide extractionUltrasound-assisted extraction (Oil extraction) | |

| Soxhlet extractionAqueous extraction (Fat extraction)Folch extraction |

Consumer Acceptance

Consumer acceptance is always a barrier to insect consumption. A wide range of factors influences consumer acceptance of edible insects as food, all of which play an important role in shaping attitudes and behaviours toward insect consumption. Disgust, food neophobia, familiarity, visibility of insects, and taste have a significant impact on consumer willingness to incorporate insects into their diets.47, 48Lack of knowledge about entomophagy is also regarded as a major reason for rejection of insect foods.49 Providing consumers with positive tasting experiences and information about the benefits of eating insects can increase familiarity and acceptance.50 People are hesitant to incorporate insects as a whole, so insect flours could be used to disguise insects in food products to increase acceptance. Consumer acceptance of insect-based foods is influenced by sociodemographic factors such as gender, age, education level, and household income. A study of Hungarians found that men were more willing to try new things and were less neophobic than women. Most women over the age of 60 did not support entomophagy. The government can change people's attitudes toward insect edibles by promoting novel products in the market.51 The marketing mix, including product development, pricing, promotion strategies, and retail placement in supermarkets, plays a crucial role in promoting consumer acceptance of insect-based products. Increasing the availability and accessibility of insect-based food products, along with positive marketing efforts, is crucial for fostering consumer willingness to try and purchase them. Most people believe that eating insects is revolting, and this idea has become ingrained in their minds, making it difficult to go. As a result, nutritional composition, increased education, and degustation sections are required to persuade people that insect foods are not harmful but rather beneficial. Exposure to insect-based foods can lead to increased acceptance and decreased reluctance towards them over time. People believe insects are unclean. As shown by studies, disgust is not a valid reason to avoid sustainable foods, as frogs and lobsters, which were once considered junk food, are now considered fine dining in many countries.52 Food preferences are formed from childhood, making it difficult to change one's mind and accept any food. Promoting entomophagy is unavoidable, but it takes time to persuade people because it is their choice whether or not to consume insects. Understanding these factors is important for increasing consumer acceptance of edible insects and advancing sustainable food systems.53

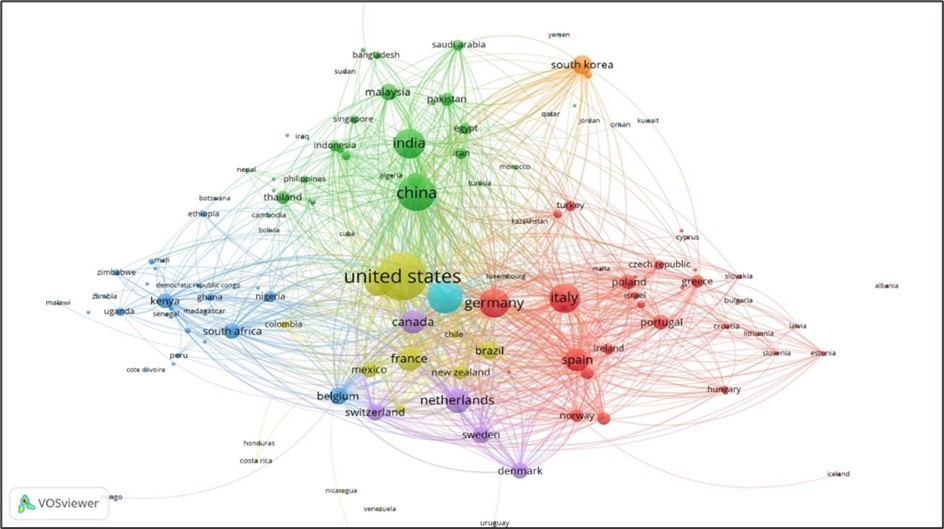

The Table 8 provides a comprehensive bibliometric and scientometric analysis of research related to edible insects, consumer acceptance, environmental sustainability, sustainable food sources, and nutritional composition, Figure 3 highlighting the geographical distribution of published articles, total number of co-authorships, and citations. The United States leads in all three categories with 4209 published articles, 38029 co-authorships, and 1026654 citations, indicating its prominent role and impact in this research domain. China and the United Kingdom also show significant contributions with 2500 and 2092 articles, respectively, and high citation counts of 446313 and 545559. Other notable contributors include India, Italy, Germany, Australia, the Netherlands, France, and Canada, each with substantial research outputs and collaborative efforts. The data suggests that European countries such as Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and France are particularly strong in research collaboration, as evidenced by their high co-authorship numbers. Overall, this analysis underscores the significant global interest and collaborative efforts in the study of sustainable food sources and their acceptance, with the United States, China, and the United Kingdom leading in research impact and output.

| Rank | Published Articles | Total No. of Co-authorship | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United states (4209) | United states (38029) | United states (1026654) |

| 2 | China (2500) | Italy (29095) | United Kingdom (545559) |

| 3 | United Kingdom (2092) | United Kingdom (27660) | China (446313) |

| 4 | India (1726) | Germany (27535) | Australia (380975) |

| 5 | Italy (1681) | Netherlands (27354) | Germany (352252) |

| 6 | Germany (1626) | China (22366) | India (297985) |

| 7 | Australia (1416) | Australia (17959) | Canada (287589) |

| 8 | Netherlands (1134) | France (15606) | Netherlands (283615) |

| 9 | France (1098) | India (13885) | France (246408) |

| 10 | Canada (1092) | Switzerland (13225) | Italy (215179) |

Figure 3.Geographical distribution of countries who have contributed in the field related to the subject areas; edible insects, consumer acceptance, environmental sustainability, sustainable food sources, and nutritional composition.

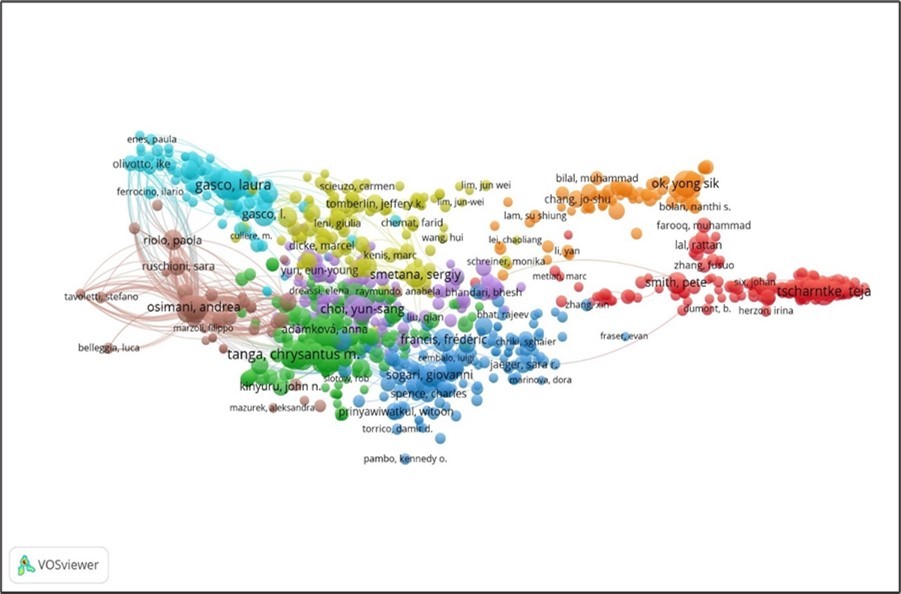

Figure 4 represents authors across world who have contributed in the field of edible insects, consumer acceptance, environmental sustainability, sustainable food sources, and nutritional composition. The Table 9 provides a comprehensive analysis of the most productive and influential authors in the field of edible insects, consumer acceptance, environmental sustainability, sustainable food sources, and nutritional composition. Among the top 10 most productive authors, Laura Gasco and Chrysantus M. Tanga lead with 50 published articles each, highlighting their significant contributions and collaborative efforts, as indicated by their high co-authorship numbers (2743 and 887, respectively). Teja Tscharntke, with 40 documents and an impressive 9365 citations, stands out for the substantial impact of his work. Similarly, Yong Sik Ok, with 39 publications and 18143 citations, is highly influential, underscoring the critical reception of his research. Other notable contributors include Sevgan Subramanian and Sunday Ekesi, who have 39 and 36 documents respectively, reflecting their active engagement in this research domain.

Figure 4.Authors who have contributed in the field of edible insects, consumer acceptance, environmental sustainability, sustainable food sources, and nutritional composition.

| Rank | Author | Documents | Citations | Total no. of Co- Authorship |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | gasco, laura | 50 | 3069 | 2743 |

| 2 | tanga, chrysantus m. | 50 | 1044 | 887 |

| 3 | tscharntke, teja | 40 | 9365 | 1313 |

| 4 | ok, yong sik | 39 | 18143 | 469 |

| 5 | subramanian, sevgan | 39 | 789 | 686 |

| 6 | ekesi, Sunday | 36 | 1167 | 772 |

| 7 | choi, yun-sang | 36 | 1049 | 1232 |

| 8 | smetana, sergiy | 35 | 1547 | 1215 |

| 9 | osimani, andrea | 34 | 1323 | 2924 |

| 10 | aquilanti,lucia | 32 | 1155 | 2809 |

In terms of influence in Table 10 measured by citations, David Tilman tops the list with 22855 citations from just 13 documents, signifying groundbreaking work. Yong Sik Ok appears again, reinforcing his dual role as both productive and highly cited. Johan Rockström and Jason Hill, with fewer documents (8 and 5, respectively), have garnered substantial citations (16060 and 14293), highlighting the profound impact of their research. This analysis underscores the significant global efforts and contributions of these leading researchers in advancing the understanding and application of sustainable food systems, with a particular focus on edible insects, sustainability, and nutrition.

Table 10. Top 10 most influential authors in terms of number of citations.| Rank | Author | Documents | Citations | Total no. of Co- Authorship |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | tilman, david | 13 | 22855 | 308 |

| 2 | ok, yong-sik | 39 | 18143 | 469 |

| 3 | rockstrom,johan | 8 | 16060 | 151 |

| 4 | hill, jason | 5 | 14293 | 209 |

| 5 | bennett, elena m. | 9 | 13609 | 77 |

| 6 | lehmann, johannes | 10 | 13076 | 94 |

| 7 | chisti, yusuf | 5 | 12352 | 83 |

| 8 | lal,r. | 11 | 12224 | 126 |

| 9 | smith, pete | 26 | 11314 | 284 |

| 10 | polasky,stephen | 5 | 9457 | 50 |

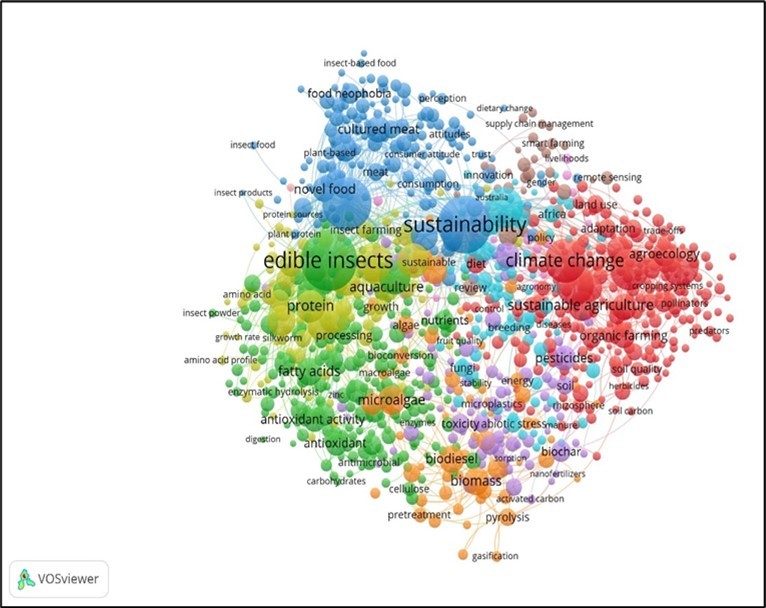

The Figure 5 and Table 11 provides a detailed overview of the primary author keywords in the research domain encompassing edible insects, consumer acceptance, environmental sustainability, sustainable food sources, and nutritional composition. The keyword "Edible insects" has the highest occurrences (817) and frequency (1929), indicating a significant focus on the role of insects as a food source. "Sustainability" follows closely with 721 occurrences and a slightly higher frequency of 1952, reflecting the critical importance of sustainable practices in food systems research. "Entomophagy," which involves the practice of eating insects, is also a major area of interest with 604 occurrences and 1592 frequency, highlighting studies on consumer acceptance. Other notable keywords include "Climate change" (422 occurrences, 1044 frequency), "Biodiversity" (381 occurrences, 1018 frequency), and "Food security" (378 occurrences, 1017 frequency), indicating strong links between insect-based food sources and broader environmental and socio-economic issues. Additionally, keywords such as "Agriculture" (357 occurrences, 1043 frequency), "Ecosystem services" (343 occurrences, 810 frequency), "Insects" (328 occurrences, 899 frequency), and "Nutrition" (265 occurrences, 799 frequency) illustrate the multifaceted research exploring the agricultural, ecological, and nutritional dimensions of using edible insects as a sustainable food source.

Figure 5.Core Author Keywords in Edible Insects, Consumer Acceptance, and Environmental Sustainability Research.

| Keywords | Occurrences | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Edible insects | 817 | 1929 |

| Sustainability | 721 | 1952 |

| Entomophagy | 604 | 1592 |

| Climate change | 422 | 1044 |

| Biodiversity | 381 | 1018 |

| Food security | 378 | 1017 |

| Agriculture | 357 | 1043 |

| Ecosystem services | 343 | 810 |

| Insects | 328 | 899 |

| Nutrition | 265 | 799 |

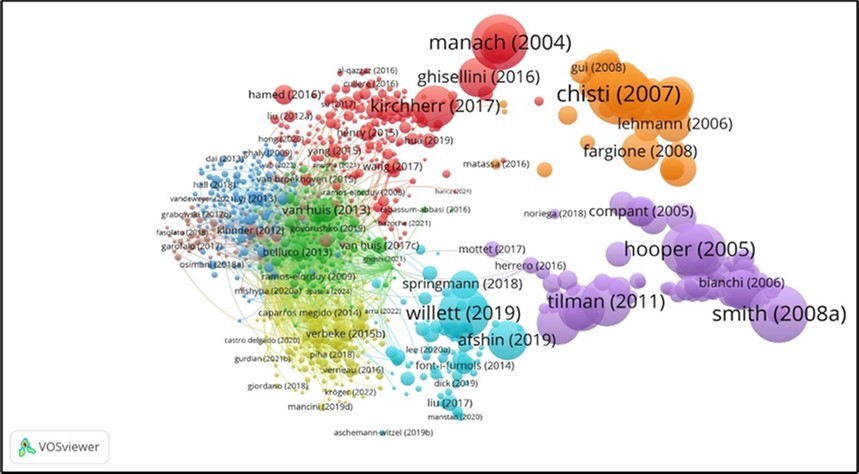

Figure 6 and Table 12 highlights the top 10 key contributing documents in the field of edible insects, consumer acceptance, environmental sustainability, sustainable food sources, and nutritional composition, ranked by their citation count. Leading the list is van Huis (2013) with 1186 citations, underscoring its foundational impact on the field. Following this, Verbeke (2015b) and Belluco (2013) have 554 and 503 citations respectively, indicating their significant contributions to consumer acceptance and nutritional studies. Hartmann (2015a) and Tan (2015a) are also highly influential, with citations reflecting their pivotal role in understanding consumer attitudes and sustainable practices. Klunder (2012) and House (2016) further contribute to the discourse on environmental and nutritional benefits. Melgar-Lalanne (2019), despite being a more recent publication, shows a growing influence with 248 citations. Caparros Megido (2014) and Looy (2014) round out the list, each providing critical insights into the practical applications and ecological impacts of edible insects. This ranking emphasizes the diverse and significant research that has shaped the understanding and acceptance of edible insects as sustainable food sources.

Figure 6.Key Contributing Documents in the Field of Edible Insects, Consumer Acceptance, Environmental Sustainability, Sustainable Food Sources, and Nutritional Composition.

| Rank | Documents | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | van huis (2013) | 1186 |

| 2 | verbeke (2015b) | 554 |

| 3 | belluco (2013) | 503 |

| 4 | hartmann (2015a) | 383 |

| 5 | tan (2015a) | 353 |

| 6 | klunder (2012) | 324 |

| 7 | house (2016) | 265 |

| 8 | melgar-lalanne (2019) | 248 |

| 9 | caparros megido (2014) | 292 |

| 10 | looy (2014) | 270 |

Conclusion

Edible insects are a highly promising alternative to traditional protein sources due to their high nutritional value, efficient resource use, and low environmental impact. They can contain high levels of protein, essential amino acids, healthy fats, and important micronutrients, making them useful in combating global food insecurity and malnutrition. Furthermore, insect farming uses less land, water, and feed than conventional livestock farming, making it a more sustainable option for future food systems.

However, before insect-based foods can be widely accepted and integrated into human diets, several challenges must be overcome. Potential health risks, such as allergic reactions (particularly in shellfish allergy patients), microbial contamination, and chemical residues, must all be carefully managed. Clear quality assurance standards are required to govern farming, processing, and storage practices and ensure food safety. Legal and standardization issues remain critical, as only a few insect species have been approved for human consumption under frameworks such as the European Union's Novel Food Regulation, and many countries still lack formal guidelines. Moving forward, strong policies and strategies are needed to support the insect industry, including government investment, consumer awareness campaigns, and the development of standard frameworks for safe and efficient production. Furthe more, dedicated research infrastructure will be required to investigate the variations in nutritional co position, the effects of processing on nutrients and shelf life, and consumer acceptance across cultures.

References

- 1.S A Babarinde, S O Binuomote, A O, K A, A et al. (2024) Determinants of the Use of Insects as Food Among Undergraduates in South-Western Community of Nigeria. Future Foods. 9, 100284-10.

- 2.Godfray H C J, J R Beddington, I R Crute, Haddad L, Lawrence D et al. (2010) . Food Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People. Science 327-812.

- 3.Clark M, Tilman D. (2017) Comparative Analysis of Environmental Impacts of Agricultural Production Systems, Agricultural Input Efficiency. , and Food Choice. Environ. Res. Lett 12, 064016-10.

- 4.B A Rumpold, O K Schlüter. (2013) Nutritional Composition and Safety Aspects of Edible Insects. , Mol. Nutr. Food Res 57, 802-823.

- 5.Payne C L R, Scarborough P, Rayner M, Nonaka K. (2016) Are Edible Insects More or Less ‘Healthy’ Than Commonly Consumed Meats? A Comparison Using Two Nutrient Profiling Models Developed to Combat Over- and. 70, 285-291.

- 6.O T Alamu, A O, C I Nwokedi, O A, I O Lawa. (2013) Diversity and Nutritional Status of Edible Insects in Nigeria: A Review. , Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv 5, 215-222.

- 7.Imathiu S. (2020) Benefits and Food Safety Concerns Associated with Consumption of Edible Insects. , NFS J 18, 1-11.

- 8.Fels‐Klerx H J Van der, Camenzuli L, Belluco S, Meijer N, Ricci A. (2018) Food Safety Issues Related to Uses of Insects for Feeds and Foods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 17, 1172-1183.

- 9.Schlüter O, Rumpold B, Holzhauser T, Roth A, R F Vogel et al. (2017) . Safety Aspects of the Production of Foods and Food Ingredients from Insects. Mol. Nutr. Food Res 61, 1600520-10.

- 10.House J. (2016) Consumer Acceptance of Insect-Based Foods in the Netherlands: Academic and Commercial Implications. Appetite. 107-47.

- 11.Zielińska E, Baraniak B, Karaś M, Rybczyńska K, Jakubczyk A. (2015) Selected Species of Edible Insects as a Source of Nutrient Composition. Food Res. Int. 77, 460-466.

- 12.Cortazar-Moya S, Mejía-Garibay B, López-Malo A, J I Morales-Camacho. (2023) Nutritional Composition and Techno-functionality of Non-defatted and Defatted Flour of Edible Insect Arsenura armida. Food Res. Int. 173-113445.

- 13.C O Atowa, B C Okoro, E C Umego, A O, Emmanuel O et al. (2021) Nutritional Values of Zonocerus variegatus. Macrotermes bellicosus and Cirina forda Insects: Mineral Composition, Fatty Acids and Amino Acid Profiles. Sci. Afr 12, 00798-10.

- 14.Baiano A. (2020) Edible Insects: An Overview on Nutritional Characteristics, Safety, Farming, Production Technologies, Regulatory Framework, and Socio-Economic and Ethical Implications. Trends Food Sci. Technol 100-35.

- 15.A M Liceaga, J E Aguilar-Toalá, Vallejo-Cordoba B, A F González-Córdova, Hernández-Mendoza A. (2022) Insects as an Alternative Protein Source. , Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol 13, 10-1146.

- 16.Melgar-Lalanne G, A J Hernández-Álvarez, Salinas-Castro A. (2019) Edible Insects Processing: Traditional and Innovative Technologies. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 18, 10-1111.

- 17.Pilco-Romero G, A M Chisaguano-Tonato, M E Herrera-Fontana, L F Chimbo-Gándara, Sharifi-Rad M et al. (2023) House Cricket (Acheta domesticus): A Review Based on Its Nutritional Composition, Quality, and Potential Uses in the Food Industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol 104226-10.

- 18.F G Hall, A M Liceaga. (2021) Isolation and Proteomic Characterization of Tropomyosin Extracted from Edible Insect Protein. Food Chem. , Mol. Sci 3, 100049-10.

- 19.Giampieri F, J M Alvarez‐Suarez, Machì M, Cianciosi D, M D Navarro‐Hortal et al. (2022) Edible Insects: A Novel Nutritious, Functional, and Safe Food Alternative. Food Front. 3, 358-365.

- 20.L A Oliveira, Pereira S M S, K A Dias, da Silva Paes, Grancieri S et al. (2024) . Nutritional Content, Amino Acid Profile, and Protein Properties of Edible Insects (Tenebrio molitor and Gryllus assimilis) Powders at Different Stages of 125-105804.

- 21.L R Dourado, P M Lopes, V K Silva, Carvalho F L A, F A Moura et al. (2020) . , Chemical Composition and Nutrient Digestibility of Insect Meal for Broiler. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc 92-10.

- 22.Mancini S, Mattioli S, Paolucci S, Fratini F, Bosco Dal et al. (2021) . Effect of Cooking Techniques on the In Vitro Protein Digestibility, Fatty Acid Profile, and Oxidative Status of Mealworms (Tenebrio molitor). Front. Vet. Sci 8, 675572-10.

- 23.Mozhui L, L N Kakati, Kiewhuo P, Changkija S. (2020) Traditional Knowledge of the Utilization of Edible Insects in Nagaland, North-East India. Foods. 9-852.

- 24.Zhao M, C Y Wang, Sun L, He Z, P L Yang et al. (2021) Edible Aquatic Insects: Diversities, Nutrition, and Safety. Foods. 10, 3033-10.

- 25.Zhou Y, Wang D, Zhou S, Duan H, Guo J et al. (2022) Nutritional Composition, Health Benefits, and Application Value of Edible Insects: A Review. Foods. 11, 3961-10.

- 26.Mohan K, A R Ganesan, Muralisankar T, Jayakumar R, Sathishkumar P et al. (2020) Recent Insights into the Extraction, Characterization, and Bioactivities of Chitin and Chitosan from Insects. Trends Food Sci. Technol 105-17.

- 27.Abidin Zainol, A N, Kormin F, Abidin Zainol, A N et al. (2020) The Potential of Insects as Alternative Sources of Chitin: An Overview on the Chemical Method of Extraction from Various Sources. , Int. J. Mol. Sci 21(14), 4978-10.

- 28.S A, Asante K, Ngah N, Y R Saraswati, Y S Wu et al. (2024) Edible Dragonflies and Damselflies (Order Odonata) as Human Food–A Comprehensive Review. J. Insects as Food Feed. 1, 1-26.

- 29.Chakravorty J, Ghosh S, V B Meyer-Rochow. (2013) Comparative Survey of Entomophagy and Entomotherapeutic Practices in. , Six Tribes of Eastern Arunachal Pradesh (India). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed 9, 1-12.

- 30.Ssepuuya G, I M Mukisa, Nakimbugwe D. (2017) . Nutritional Composition, Quality, and Shelf Stability of Processed Ruspolia nitidula (Edible Grasshoppers). Food Sci. Nutr 5(1), 103-112.

- 31.B A Rumpold, Fröhling A, Reineke K, Knorr D, Boguslawski S et al. (2014) . Comparison of Volumetric and Surface Decontamination Techniques for Innovative Processing of Mealworm Larvae (Tenebrio molitor). Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol 26, 232-241.

- 32.Ordoñez-Araque R, Sandoval-Cañas G, E F Landines-Vera, Criollo-Feijoo J, Casa-López F. (2024) Sustainability and Economic Aspects of Insect Farming and Consumption. In Insects as Food and Food Ingredients; 47-63.

- 33.Herrero M, Havlík P, Valin H, Notenbaert A, M C Rufino et al. (2013) Biomass Use, Production, Feed Efficiencies, and Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Global Livestock Systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110(52), 20888-20893.

- 34.Steinfeld H, Gerber P, Wassenaar T, Castel V, Rosales M et al. (2006) Livestock's Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options. Food & Agriculture Org.:. , Rome

- 35.A Van Huis, D G Oonincx.The Environmental Sustainability of Insects as Food and Feed: A Review. , Agron. Sustain. Dev 2017, 1-14.

- 37.Collavo A L B E R T O, R H Glew, Y S Huang, L T Chuang, Bosse R E B E C C A et al. (2005) House cricket small-scale farming. , Ecol. Implic. Minilivestock: Potent. Insects, Rodents, Frogs Snails 27, 515-540.

- 38.Smil V. (2002) Worldwide Transformation of Diets, Burdens of Meat Production and Opportunities for Novel Food Proteins. Enzyme Microb. Technol 30(3), 305-311.

- 39.Offenberg J. (2011) Oecophylla smaragdina Food Conversion Efficiency: Prospects for Ant Farming. , J. Appl. Entomol 135, 575-581.

- 40.Pimentel D, Berger B, Filiberto D, Newton M, Wolfe B et al. (2004) Water Resources: Agricultural and Environmental Issues. BioScience. 54, 909-918.

- 41.A K Chapagain, A Y Hoekstra. (2003) Virtual Water Flows Between Nations. in Relation to Trade in Livestock and Livestock Products (Vol. 13) , Delft, The Netherlands: UNESCO-IHE .

- 42.Govorushko S. (2019) Global Status of Insects as Food and Feed Source: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol 91, 436-445.

- 43.Obopile M, T G Seeletso. (2013) Eat or Not Eat: An Analysis of the Status of Entomophagy in Botswana. Food Sec. 5, 817-824.

- 44.Liang Z, Zhu Y, Leonard W, Fang Z. (2024) . Recent Advances in Edible Insect Processing Technologies. Food Res. Int. 114137. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.114137 .

- 45.Zhen Y, Chundang P, Zhang Y, Wang M, Vongsangnak W et al. (2020) . Impacts of Killing Process on the Nutrient Content, Product Stability and In Vitro Digestibility of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae Meals. Appl. Sci 10(17), 6099-10.

- 46.R O Lamidi, Jiang L, P B, Wang Y, A P Roskilly. (2019) Recent Advances in Sustainable Drying of Agricultural Produce: A Review. , Appl. Energy 233, 367-385.

- 47.S M Kauppi, I N Pettersen, Boks C. (2019) Consumer Acceptance of Edible Insects and Design Interventions as Adoption Strategy. , Int. J. Food Des 4(1), 39-62.

- 48.M C Onwezen, Puttelaar J Van den, Verain M C D, Veldkamp T. (2019) Consumer Acceptance of Insects as Food and Feed: The Relevance of Affective Factors. Food Qual. Prefer 77, 51-63.

- 49.Zielińska E, Zieliński D, Karaś M, Jakubczyk A. (2020) Exploration of Consumer Acceptance of Insects as Food in. 6(4), 383-392.

- 50.Sogari G, Dagevos H, Amato M, Taufik D. (2022) Consumer Perceptions and Acceptance of Insects as Feed and Food: Current Findings and Future Outlook. In Novel Foods and Edible Insects in the European , Cham 147-169.

- 51.Kasza G, Izsó T, Szakos D, W S Nugraha, M H Tamimi et al. (2023) Insects as Food - Changes. in Consumers’ Acceptance of Entomophagy in Hungary between 2016 and 2021. Appetite 188-106770.